John O’Neill

The Printing of the Second Part of Don Quijote and Ocho comedias: Evidence of a Late Change in Cervantes’s Attitude to Print and of Concurrent Production as Practised by both Author and Printers

The Library, Volume 16, Issue 1, March 2015, Pages 3–23, https://doi.org/10.1093/library/16.1.3

Published: 26 March 2015

THE TITLE OF CERVANTES’S Ocho comedias y ocho entremeses nuevos, nunca representados (‘Eight New Plays and Interludes, Never Performed’) provides us with an ironic reminder of his failure as a playwright in his later years.1 In the prologue he elaborates on the reasons for his inability to find an audience for his plays, telling us that, although he had enjoyed some success with the works for the stage that he wrote in the 1580s, his later plays, completed in the early part of the seventeenth century—by which time the new style of theatre championed by Lope de Vega and his followers held sway—did not arouse any interest amongst the autores, the all-powerful actor-managers who determined the repertoire of the theatre companies:

I did not find an actor-manager who wanted them, even though they knew I had them; and so I threw them into a chest, consigning and condemning them to perpetual silence. At the time a bookseller informed me that he would have bought them, had an actor-manager of some note not told him that much could be expected of my prose, but of my verse nothing.2

For much of the period of four hundred years that has passed since their publication, Cervantes’s plays have continued to attract much less attention than his prose fiction, although in recent years there have been signs that the originality of his theatre is gradually becoming more widely acknowledged. Jonathan Thacker, for example, states that Cervantes is ‘a far more important dramatic voice than has habitually been recognized’, and Pedro, The Great Pretender, Phillip Osment’s translation of Pedro de Urdemalas, was included in the Royal Shakespeare Company’s Golden Age season of 2004.3 Most critics, however, still consider Cervantes to be a much less significant dramatist than the famous triumvirate of Lope de Vega, Tirso de Molina, and Calderón de la Barca, and that opinion is reflected in the fact that many of the full-length plays have yet to be either translated or performed.

The first edition of Ocho comedias, like the plays themselves, has generated little interest, yet the preliminares, or front matter, of this volume reveal a connection with the second part of Don Quijote that is of interest both to students of Cervantes and to bibliographers in general.4 The purpose of this study is to investigate the significance of that connection—a process that has involved looking at the difficult conditions under which Cervantes wrote and his changing attitude to print, and analyzing data relating to books produced at two different Madrid print-shops during a period of four years from the beginning of 1612 to the end of 1615. The results of the research provide new insights into the working practices both of Cervantes and of his printers, challenging assumptions that have been made about modes of production in Spanish printing-houses during the early-modern period, and thereby supplying an answer to a question that has been raised about the length of time it took to print the second part of the Quijote.

The items usually included in the preliminares were the privilegio or licencia, the fe de erratas, the tasa, and the aprobación. There might also be a prologue and a dedication to the author’s patron, as was the case with both of Cervantes’s books. A licencia was simply a licence to print the work, whereas the privilegio gave exclusive rights of publication to the author for a limited period—twenty years for the second part of the Quijote and ten years for Ocho comedias. The author could—and usually did—sell the privilegio to a bookseller, who would then make a contract with a printer.5 The fe de erratas was not, as one might perhaps expect, a list of typographical errors, but an official testimony that the printed work was a faithful copy of the original de imprenta, a transcription of the author’s manuscript prepared for the printer by a scribe, which had to be submitted to the censor for approval (the aprobación). The date of the fe de erratas therefore indicates when the printing of the body of the work was finished.6 The process of production was not, however, quite complete, since the fe de erratas was usually followed, in most cases just a few days later, by the tasa— the setting of the selling price of the book—although in some cases the order is reversed and the tasa precedes the fe de erratas. In certain books other material from the front matter may also carry a later date than the tasa. For example, in the second part of Don Quijote the dedication was signed by Cervantes on 31 October, ten days after the tasa and fe de erratas, and the final date in the preliminares is 5 November, when Gutierre de Cetina signed the third aprobación.

Printing normally began only after the privilegio had been granted.7 It would have been in the interests of all parties—author, bookseller, and printer—that this should be as soon as possible, but the precise date on which production began may have depended on other factors, such as the other work that the printer had on hand. Since printing was generally completed—with the possible exception of certain other items in the preliminares—by the date of the fe de erratas, the period between the dates of the privilegio and the fe de erratas can be described as the production window— the period during which production must have occurred. In the case of the second part of Don Quijote almost seven months elapsed from the granting of the privilegio, on 30 March 1615, to the signing of the fe de erratas, on 21 October.8 That was more than twice the length of time it took to produce the first part—a significantly bigger book financed by the same bookseller, Francisco de Robles, and produced at the same print-shop, the one that bore the name of Juan de la Cuesta, but was actually owned by María Rodríguez de Ribalde.9

Returning to the preliminares of Ocho comedias, one finds that the privilegio for that volume was granted on 25 July 1615 and that the fe de erratas is dated 13 September, which means that, while the second part of Don Quijote was in production, the printing of the collection of plays, financed by a different bookseller, Juan de Villarroel, was completed at another print-shop, that of ‘La viuda de Alonso Martín’ (the widow of Alonso Martín), in just two months.10 Ocho comedias consists of sixty-five sheets of quarto, five fewer than the second part of Don Quijote, but it would have been a far more complex project for a printer to set the volume of eight plays and interludes, especially since the full-length plays were written in a number of different verse forms.

If the unnamed bookseller mentioned in the prologue to Ocho comedias as having rejected the plays were Robles, that would provide us with a neat rationale for Cervantes’s placing them with another publisher and printer. However, the full explanation, it will be argued here, is more complex, and the key to understanding it, and also the delay in the production of the second part of Don Quijote, is provided by evidence that Spanish printers of this period had in place a system of concurrent production similar to the one described by McKenzie in his famous study of a Cambridge print-shop, operating over eighty years later.11 There is also strong evidence to suggest that Cervantes, who had a keen understanding of the way the printing business worked, had his own system of concurrent production in place, designed to expedite the publication of his late works. However, in order to appreciate fully the significance of the events surrounding the production of Cervantes’s works in Madrid in 1615 it is necessary first to place them in the context of his publishing history, which is characterized by a strangely uneven chronology and an uneasy relationship with print.

Few of Cervantes’s writings were published in the first sixty-five years of his life. His first novel, La Galatea, appeared in 1585, when he was thirty-seven years old.12 This pastoral romance was well received at the time, running to seven editions by 1618.13 In his aprobación to the second part of Don Quijote Francisco Márquez Torres recounts having met some French noblemen, one of whom ‘had almost managed to memorize it’.14 Even Cervantes’s rival Lope de Vega voiced his approval, through a character in La viuda valenciana (‘The Widow of Valencia’), who declares: ‘This is Galatea, if you want a good book then look no further’.15 Despite this success, twenty years passed before the publication of the first part of Don Quijote in 1605, a period that he refers to in the prologue of that work as ‘the silence of oblivion’ (‘el silencio del olvido’), and another eight years followed before the appearance of the Novelas ejemplares (‘Exemplary Stories’) in 1613.16 However, this trickle was followed by a deluge, with four more works printed in the last eighteen months of his life: Viaje del Parnaso (‘Journey to Parnassus’, November 1614), Ocho comedias (September 1615), the second part of Don Quijote (October 1615), and Persiles y Sigismunda, which he finished writing in April 1616, just before he died, and which was published posthumously early in 1617.17 Moreover, according to what Cervantes tells us in the various prol ogues and dedications of these late works, he was preparing three more works for publication when he died: the second part of La Galatea, Semanas del jardín (‘Weeks in the Garden’), and Bernardo. This late flurry of activity becomes even more remarkable when we consider that Cervantes was not only in his mid to late sixties but suffering from chronic ill-health with oedema.

The story of the printing of Cervantes’s works is, therefore, a curious one: sixty-five years of relative inactivity followed by a frenetic three years in which he seemed determined to publish as much as possible. The long gap between La Galatea and Don Quijote can, at least in part, be explained by the circumstances of his life, for during much of this period, from 1587 until 1597 or later, he was working as a government civil servant in Andalusia, first as a commissary for supplies for the Armada and then as a tax collector. These were demanding and stressful jobs, involving a lot of traveling and a considerable amount of paperwork, which would have left him with less time for writing. The period of eight years between Don Quijote and the Novelas ejemplares is, however, more difficult to account for. Why did Cervantes not seek to build on the extraordinary success of the Quijote, which had made him the most famous writer of prose fiction in Europe? The answer probably lies in the reservations he felt about the medium of print, which he expresses on two different points in the second part of Don Quijote: in the conversation between Don Quixote and Sansón Carrasco in Chapter 3, which I will return to later, and during Don Quixote’s visit to the Barcelona Print-shop in Chapter 62.

Don Quixote’s visit to a Barcelona print-shop in Chapter 62 indicates that Cervantes was very familiar not only with the technical aspect of printing but also with the way the business worked.18 Don Quixote witnesses the key activities that take place—composition of the formes by the typesetters, the operation of the presses, and correction of the proofs—and then strikes up a conversation with a man who is having his translation of an Italian work called Le Bagatele (sic) printed there. The translator, who is determined to have his book printed at his own expense, responds as follows to Don Quixote’s warning that he may end up with a lot of unsold copies on his hands, as a result of the shenanigans of printers: ‘“Well what would you have me do?”, said the author. “Do you want me to sell the rights to a bookseller, who’ll give me three maravedís for them and think he’s doing me a favour?”’19 It is a complaint that is echoed in Chapter 1 of the Fourth Book of Persiles y Sigismunda, by a Spanish pilgrim, whom Periandro and Auristela encounter in an inn near Rome, who is writing a book of aphorisms:

I won’t give up the rights to my book to any bookseller in Madrid even if he pays two thousand ducados for them. There isn’t a single one of them there who doesn’t want the rights for free, or for such a low price that it doesn’t benefit the author of the book.20

The translator’s experience probably reflects that of Cervantes, who had recently financed the printing of Viaje del Parnaso out of his own pocket, and who had ample experience of how little money could be made from writing novels and how the odds were stacked in favour of the bookseller when it came to selling the privilegio. In June 1584 Blas de Robles agreed to pay him 1336 reales for the rights to La Galatea, yet just eighteen months later he was in such dire straits that he needed to borrow more than four times that amount—204,000 maravedís, or 6,000 reales—in order to settle a debt.21 The success of Don Quijote had brought fame, but not riches, for even that bestseller, which ran to two editions in the first year, had earned him very little. He had sold the rights to the bookseller Francisco de Robles for 1500 reales, which, bearing in mind the rampant inflation that the Spanish economy was experiencing at the time, was probably an even worse deal than the one he had struck for Galatea.22 While the fact that he had not published anything for twenty years might explain his failing to profit from selling the privilegio of Don Quijote, it does not account for the similarly unfavourable arrangement regarding the rights to the Novelas ejemplares, which were sold on 9 September 1613 for just 1600 reales, at a time when Cervantes was famous throughout Europe.23 A playwright could make money from having their work performed on stage, but there was little profit in writing novels, even for an author as celebrated as Cervantes. In the aforementioned aprobación of the second part of Don Quijote Francisco Márquez Torres relates how, when asked by the French noblemen who were aficionados of Cervantes’s writing about the author’s ‘age, profession, status and wealth’, he replied, to their surprise, ‘old, a soldier, low-ranking nobility, and poor’ (‘viejo, soldado, hidalgo y pobre’).24 That picture of hardship is confirmed by Cervantes himself in the dedication to his patron, the Count of Lemos, in which he describes himself as ‘extremely hard-up’ (‘muy sin dineros’).25 These words, and those of Márquez Torres, who was a chaplain employed by the Archbishop of Toledo, one of Cervantes’s benefactors, are an ironic reminder that, while patronage may have eased his financial situation somewhat, it certainly did not make him comfortable.

Since the vast majority of the profits from printed books went to the bookseller, and since Cervantes, for most of his life, received little or no benefit from patronage, he had no great financial incentive to have his writings printed. The possibility of achieving celebrity was, of course, another motive, as Cervantes indicates in the prologue to the second part of Don Quijote:

I know only too well the temptations of the devil, and one of the greatest is to put the idea in a man’s mind that he can write and print a book that will earn him as much fame as money and as much money as fame.26

Here, and in the conversation between Don Quixote and the translator in the print-shop, Cervantes seems to be suggesting that the writer needs to choose between fame or profit. The translator makes it clear that his motives are purely mercenary: ‘I do not have my books printed to attain fame in the world, for I am already known for my work. I want profit. Without it, fame is not worth a farthing’.27 Choosing literary celebrity, however, as Cervantes had done, also involved risks, as we are reminded by the fact that the remarks in the prologue to the second part of Don Quijote are directed at an unknown writer going by the pseudonym of Alonso Fernández Avellaneda, who, in the autumn of 1614, had published a hostile sequel to the first part, in the prologue of which he had launched a vitriolic attack on Cervantes.28 The hijacking of his literary creation outraged Cervantes to such an extent that he changed the timetable that he had planned for the publication of his works, suspending work on Persiles to bring forward the completion of the Quijote. He expressed his contempt for Avellaneda at various points throughout the text, for example in the episode in the print-shop, which ends with the knight storming out, piqued by his discovery that one of the works being produced there is Avellaneda’s Quijote.

Don Quixote thinks Avellaneda’s book should have been ‘burned to cinders for its impertinence’ (‘quemado y hecho polvos por impertinente’), and goes on to stress the importance of truth in fiction.29 However, the book-trade does not make a distinction between works of fiction that are true and those which are false, and that lack of discrimination clearly infuriated Cervantes. It also irritated him that it was the publication of Don Quijote that had given rise to Avellaneda’s apocryphal sequel, as is clear from one of the items in Don Quixote’s last will and testament:

Item: I beseech the aforementioned gentlemen my executors that if by chance they should meet the author who is said to have composed a story that goes by the name of The Second Part of the Adventures of Don Quixote of La Mancha, they should, on my behalf, ask him, as insistently as possible, to pardon me for unthinkingly having given him the opportunity to write such a load of claptrap, because I leave this life with pangs of conscience for having given him the motive for writing it.30

That print could have negative consequences, and expose one to criticism or ridicule, was something that Cervantes had realized several years previously, when the first part of Don Quijote was published. It is a theme that emerges in Chapter 3 of the second part, in a conversation between Don Quixote and Sansón Carrasco, who, as the reader learns in the previous chapter, has brought news from Salamanca that Sancho and Don Quixote have become literary celebrities through the publication of the first book:

‘It often happens that those who have cultivated and achieved great fame through their writings either lose it completely or see it somewhat diminished when they hand them over to be printed.’

‘The reason for that’, said Sansón, ‘is that, as printed works are viewed at one’s leisure, it is easy to see their faults, and, the more famous the person who wrote them, the more they are subject to scrutiny.’31

Cervantes, in the Adjunta al Parnaso, the prose postscript to his narrative poem Viaje del Parnaso, is keen to stress an advantage, where plays are concerned, of the medium of print, which allows the reader to appreciate at his or her leisure what passes quickly in performance:

I am considering handing over the plays to be printed, so that one might see at one’s leisure what happens quickly, or is disguised or misunderstood when they are performed. Moreover, plays, like songs, have their seasons and their times.32

However, in the conversation between Don Quixote and Sansón, and again in the following chapter, Cervantes dwells on a major disadvantage of publication. Errors, once fixed in print, can be difficult to erase, both from the book and from the memory of the reader.

The most infamous of the faults in the first part of Don Quijote that Sansón Carrasco mentions is the narrative of the theft of Sancho’s donkey. In the first edition of Juan de la Cuesta reference is made to its having gone missing, but with no explanation as to how, between Chapters 25 and 29. In Chapter 42 the donkey reappears, again with no explanation. In the second Cuesta edition of 1605 an attempt was made to resolve the problem by inserting an episode in Chapter 23 in which Ginés de Pasamonte steals the animal, but the donkey is referred to six times, as if the theft had not occurred, before its recapture is described in Chapter 30.33 These discrepancies were all corrected in the Brussels edition of 1607, printed by Roger Velpius, but, astonishingly, only two of those corrections found their way into the third Cuesta edition of 1608.34 Cervantes decided to make light of the issue by incorporating these botched attempts at repairing the original error into the metafictional fun and games that characterize the second part of Don Quijote. When Sansón remarks that ‘before the ass reappeared the author states that Sancho was riding it’, Sancho retorts that ‘either the chronicler was mistaken, or it was carelessness on the part of the printer’, thus laying the blame on the fictional narrator, Cide Hamete Benengeli, or the actual print-shop of Juan de la Cuesta.35 That Cervantes felt the need to address the issue ten years after the error had first appeared in print demonstrates how much it bothered him. However, if he thought that his authorial sleight of hand would spare him further embarrassment, he was mistaken. Lope de Vega, who had been angered by some disparaging comments that Cervantes made in Chapter 42 of the first part, concerning his commercial attitude to the theatre, was certainly not inclined to let his rival off the hook. In Act III of Amar sin saber a quién (‘Loving, Without Knowing Who’) he refers not just to the original mistake, but to Cervantes’s attempts at exculpating himself, when the gracioso Limón, regarding the loss of an ass, says: ‘Tell us its colour, shape and name, for there is a man who is still waiting to find out what happened to a brownish grey mule. If you don’t, they will say it was “forgetfulness on the writer’s part”.’36 For Chartier the textual inconsistencies in the narration of the theft of Sancho’s donkey ‘point up the similarities that exist between Cervantes’s writing and certain practices of orality’.37 However, while such errors may have been part and parcel of the episodic, oral approach to storytelling in which Cervantes excelled, once fixed in print they laid him open to ridicule.

Cervantes therefore had good reason to develop ambivalent feelings about the medium of print, for although it made him famous, it also exposed him to criticism, some of it vicious, gave Avellaneda the opportunity to kidnap his hero, and made him very little money. However, in the period leading up to the publication of the Novelas ejemplares in 1613 any reservations that he felt about print probably began to be outweighed by a growing awareness, as a result of his age and ill health, of his own mortality, and the knowledge that the printed book was the only means whereby he could ensure that his writings would be preserved for posterity. Everything that he writes in the prologues and dedications of his late works is indicative of an author who is striving to complete, and have printed, as much of his work as possible. In the prologue to the Novelas he refers to Viaje del Parnaso as already having been written, even though the narrative poem was not printed until over a year later, at the end of 1614.38 He also announces that the volume of stories will be followed by Persiles, the continuation of Don Quijote and Semanas del jardín, a work that was never completed, the title of which suggests that it may have been conceived as another book of novelas.39 In the dedication to Ocho comedias he informs the Count of Lemos that ‘Don Quijote de la Mancha has put his spurs on, in his Second Part, in order to go and kiss Your Excellency’s feet’ and that Persiles, Semanas del jardín, and the second part of La Galatea will follow.40 In the prologue to the second part of Don Quijote and the dedication that follows it, dated 31 October 1615, he tells his readers to expect both Persiles, which he is ‘in the process of finishing’ and ‘will complete, God willing, within four months’, and the sequel to La Galatea, while in the dedication to Persiles, written just three days before he died, he indicates his intention to complete, if his health allows, not only Semanas del jardín and the second part of La Galatea but also Bernardo.41 Since that is the first mention of the latter work, whose title suggests a chivalric theme, it may have only existed in embryonic form.42 However, the consistency with which Cervantes refers to Semanas del jardín and the continuation of La Galatea from 1613 onwards makes it likely that these works were, indeed, at an advanced stage.

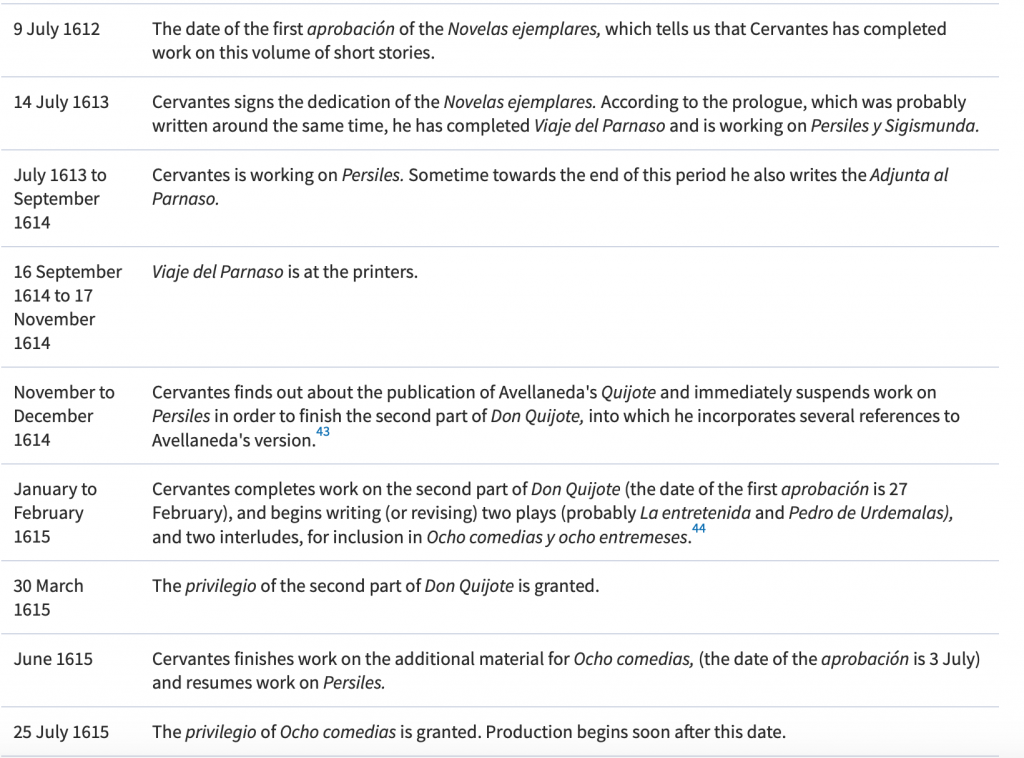

Taking into account what Cervantes himself tells us, and other information garnered from the front matter of the books written in the last few years of his life, it is possible to construct the following timetable for the production of his late works:

The schedule that Cervantes set for himself in the final four years of his life would have been demanding for any writer, but it is particularly remarkable when we consider that he was a man in his late sixties in poor health. In all but two months of the period of approximately fourteen months between mid September 1614 and early November 1615 Cervantes had at least one work at the printers. From 1612 he was not only writing continuously, but also making plans for the completion of as many as four other projects at the same time. This feverish activity reached its peak in the late summer of 1615, for, during August and September of that year, while he was writing Persiles, both the second part of Don Quijote and Ocho comedias were in production, with two different printers. Cervantes, who, as he indicates in Chapter 62 of the second part, was familiar with the ‘ins and outs of the printing business’ (‘las entradas y salidas de los impresores’), knew that printers had a system of concurrent production in place, which could produce lengthy delays.45 He had, accordingly, devised his own method of concurrent production, in order to ensure that as much of his writing as possible would be printed.

Garza Merino has stated that Spanish print-shops were organized around one major project at a time: ‘We know from surviving printing contracts that generally, once an edition had been agreed, it was a requirement that no other work would be accepted until the new one had been finished, which, barring exceptional circumstances, implied that the print-shop would organize itself around one project, apart from any small jobs that might be taken on’.46

Garza Merino is not specific about her sources, but her remarks would, at first blush, appear to be supported by a sixteenth-century document by Juan Vásquez de Mármol, the corrector at the Royal Printing-House (Imprenta de Su Majestad), listing thirteen conditions that an author could require a printer to meet before entering into a contract.47 The first of these stated that the printer was obliged to begin printing within a certain period, and not to abandon the process once begun.48 It is possible, however, to interpret that condition in different ways. An author or bookseller keen to see their book produced quickly might hope that it meant that the print-shop would focus exclusively on their job, whereas the printer could argue that dividing time between two or three jobs did not mean that the process of printing any one of them had been abandoned.49 In any case, Garza Merino’s views are clearly at odds with those of McKenzie, who, in his essay Printers of the Mind, which considered the records of the Cambridge University Press between 1696 and 1712 and of the London printing-house of Bowyer and Son between 1730 and 1739, found that ‘the Cambridge and Bowyer presses, like any other printing-house today or any other printing-house before them, followed the principle of concurrent production’, and that there was no evidence to suggest that any printing-houses of the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries did not habitually print several books concurrently.50 McKenzie’s findings are supported by what happens in the episode in the print-shop, for there Don Quixote witnesses three books being produced concurrently. The aforementioned translation of Le Bagateleis being set by a compositor, while two other books are being proofed and corrected: a work entitled Luz del alma (‘Light of the Soul’) and—much to the knight’s displeasure—Avellaneda’s Segunda parte del ingenioso hidalgo don Quijote de la Mancha.

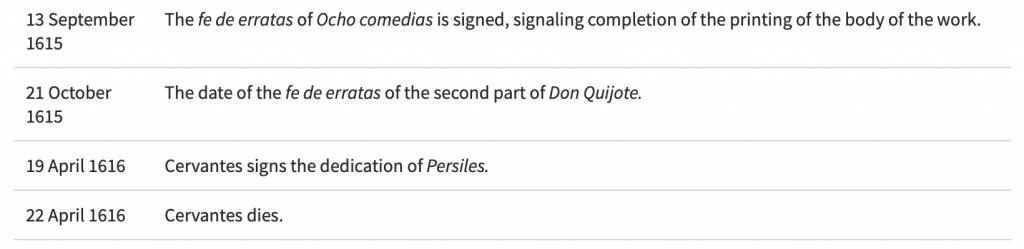

Analysis of information contained in the preliminares of sixty-five books produced at the print-shops of Juan de la Cuesta and La viuda de Alonso Martín between 1612 and 1615, obtained from Pérez Pastor’s Bibliografía madrileña, shows that printers in Madrid, like their English counterparts at the end of the seventeenth and beginning of the eighteenth centuries, and like those in the Barcelona printing-house described in the Quijote, did indeed operate a system of concurrent production. Table 1 shows part of the data that was collated: the key dates that indicate the production windows of seven other books printed at the Cuesta and Martín shops between 30 March 1615 and 5 November 1615, while Ocho comedias and the second part of Don Quijote were also in production.

The table helps to explain a question raised by Rico, who, in his study of the printing of the two parts of the Quijote, was puzzled by the fact that the second volume took so much longer to produce than the first one. The privilegio for the first part was granted on 26 September 1604, while the testimonio de las erratas is dated 1 December, which means that printing was completed in a little over two months.51 The corresponding period for the second part ran from 30 March to 21 October 1615—nearly seven months, even though the second volume is significantly shorter, at 280 folios, than the first one (316 fols.).52 Since there are more errors—almost double the number—in the second part, Rico thought it unlikely that the delay in the printing of the second part could be ascribed to a slower rate of production, and was unable to find any other explanation than bad luck, going on to say that the standard of printing in Spain at this time was incredibly low, and that print-shops were poorly equipped, undermanned, and lacking typesetters and correctors who were sufficiently qualified.53 That explanation is, however, thrown into question by Moll’s assertion that the Spanish printing industry of this period, despite facing technical problems, had a number of well equipped shops, with skilled workers who had an in-depth knowledge of their business and were capable of producing books of quality.54

It seems that Rico did not take into account concurrent production and must have assumed, like Garza Merino, that work in the print-shop would have been organized around one project. If one takes into account the other jobs with which the Cuesta shop was occupied, the real reason for the delay becomes clear. The production window of the second part of Don Quijote overlapped with that of four other works: parts V—VIII of Herrera’s Historia general; a new edition of Nebrija’s Dictionarium; Murcia de la Llana’s Compendio;and the second edition of Salas Barbadillo’s El Cavallero puntual (‘The Punctilious Knight’).55 The first two of these books were very large projects—319 and 213 sheets respectively, in folio format. Indeed, it is quite conceivable that, even though the privilegio for the second part of the Quijote was granted on 30 March, production did not get fully up to speed until the beginning of August, when work on the books by Herrera and Nebrija was completed. It would then have shared production time with the Compendio, another work in quarto, whose fe de erratas precedes that of the Quijote by only eight days, and El Cavallero puntual, a work in the comparatively rare duodecimo format, the erratas of which is dated 9 November, just four days after the final date in the front matter of the Segunda parte— the aprobación of Gutierre de Cetina.56

That the second part of the Quijote took longer to produce than the first part was therefore nothing to do with bad luck, poor equipment or insufficient manpower, but rather can be attributed to the fact that the book was printed concurrently with at least two others, and possibly as many as four. This was normal practice in the Cuesta shop during the period in question, and it was also the case in the printing-house of La viuda de Alonso Martín, where Ocho comedias was produced. As Table 1 shows, the volume of plays, comprising sixty-five sheets in quarto, was printed concurrently with three others: a book of sermons of one hundred and twelve sheets, also in quarto, and two works in octavo, the Rhetoricae Compendium ex scriptis patris Ioannis Baptistae and Ledesma’s Romancero, comprising twenty-five and twenty-four sheets respectively.57 The fact that these books were not printed serially is demonstrated by the fact that printing of the body of the four works was completed in quick succession: Ocho comedias on 13 September, the Sermones on 22 September, the Rhetoricae Compendium on 5 October, and the Romancero on 13 October.

Gaskell has summarized the reasons for concurrent production as follows: ‘Books varied so much in size that a balance between composition and presswork could not have been kept if they had been printed serially… for, depending on the relative magnitude of their tasks and on accident, either pressmen or compositors would constantly have been waiting for the others to catch up. Printers therefore had several books in production at once… so that when a man came to the end of a stage in the work, he would be in a position to take up something else’.58

This meant that an individual book took longer to print than it might have done if all the workmen had concentrated on it alone; but also that, by using plant and labour less wastefully, all the books could be printed in less time altogether, and at less cost, than they would have been by serial production.

In most cases production would not, therefore, as Garza Merino suggests, have involved two typesetters working in synchronized fashion on one book in order to supply one or two pressmen, thus ensuring that by the end of the day one sheet of a run of 1,000 or 1,500 copies had been printed.59 The organization of work would instead, as McKenzie argues, have been far more complex and varied, with typesetters and pressmen taking up whatever work was to hand, in order that they should not stand idle. What McKenzie discovered in the records of the Cambridge University Press was that each compositor would work on two or three books simultaneously, and that, even when two compositors worked on one book, the usual practice was that one would take over where the other left off. Like the compositors, a press-crew would usually be working on several books simultaneously, and the most efficient system was not to try to maintain a relationship between a particular compositor and crew.60 If the method of production in Madrid at the beginning of the seventeenth century were similar, as the evidence presented here suggests, then any study of the printing of a Spanish book from this period cannot view the production of that volume as an isolated event, but also needs to take into account other works that were printed concurrently in the same shop.

Since it was based on efficiency, the system of concurrent production worked to the advantage of both printer and author. However, writers keen to see their work published as quickly as possible would not necessarily have seen it that way. Cervantes had already experienced the frustrating delays that this mode of production involved during the printing of the Novelas ejemplares. The privilegio for that work, which was printed concurrently with Aranda’s Lugares comunes (Commonplaces) and the second part of Illescas’s Historia Pontifical y Catholica, was granted on 22 November 1612, yet the fe de erratas was not signed until 7 August 1613, over eight months later.61 By 1615 the ailing author, now sixty-seven years old, had probably realized that, if he were to achieve his ambition of publishing as much of his work as possible before he died, and, in particular, to have his beloved plays printed, he was going to need the services of more than one printer. It may well have been the case, as Cervantes hints in the prologue to Ocho comedias, that Robles, the bookseller who financed both parts of the Quijote and the Novelas ejemplares, was decidedly unenthusiastic about the idea of publishing the plays, but, even if that had not been so, Cervantes, for whom time was running out, would have been keen for him to find another printer, since the Cuesta shop was already occupied with the second part of the Quijote and the other works which were printed concurrently with it.

In the event, Cervantes managed to interest a newcomer to the book trade, the twenty-five year old Juan de Villarroel, in Ocho comedias. His shortlived career in publishing began in 1614, when he financed an edition of Juan Pérez de Moya’s Arithmetica Practica.62 He also acquired the rights to a new edition of Fernando de Mena’s translation of Heliodorus’s Historia etiopica de los amores de Teogenes y Cariclea, which appeared in the summer of 1615, just before Ocho comedias, although the title page of that volume indicates that it was financed by Pedro de Bogia.63 All of these books were printed at the print-shop of La viuda de Alonso Martín, which had been run by Francisca Medina since her husband’s death in 1613.64 Villaroel clearly ran into financial difficulties, for on 6 November 1615 there is a record of his owing 1,500 reales to Medina for the cost of printing both the Arithmetica and Ocho comedias.65 In the prologue to Ocho comedias, Cervantes mentions, with scarcely veiled irony, having been paid ‘a reasonable sum’ for the volume of plays; but he was never actually paid in full, for in 1626, nine years after his death, his widow, Catalina Palacios Salazar y Vozmediano, mentioned in her last will and testament an amount of 400 reales that Villarroel still owed.66

Medina’s print-shop was an obvious choice for the volume of plays. It was situated in Calle de los Preciados, a little further away than the Cuesta shop in Calle de Atocha, but still just a ten-minute walk from where Cervantes was living at the time, on the corner of Calle de León and Calle de Francos (now known as Calle de Cervantes), and even closer to Villarroel, whose address on the title page of Ocho comedias is given as ‘plaçuela del Angel’ (now known as Plaza del Ángel).67 The Medina shop, which printed many classic works of the Spanish Golden Age, had already produced Cervantes’s Viaje del Parnaso, and had just recently, on 3 April, completed printing of the Sexta parte (sixth part) of the plays of Lope de Vega, Spain’s most celebrated dramatist.68 Moreover, while the Cuesta shop specialized in the folio format, the printing-house of Medina was noted for working in octavo—the format in which Viaje del Parnaso appeared—and quarto, which was the usual format for plays. In 1615 it produced eight works in quarto, comprising 568 sheets, as opposed to Cuesta’s three (113 sheets). Ocho comedias, a work of sixty-five sheets, was produced in just eight weeks, with the result that although the privilegio for the plays was granted a month later than that of the Sermones and over two months later than that of Ledesma’s Romancero—the two books with which it was printed concurrently—Ocho comedias was the first of the three works to be completed. The privilegio for the plays was granted four months later than that of the second part of Don Quijote, yet the production of the plays was completed six weeks before the printing of the novel was finished. The efficiency of the Medina print-shop was such that, on 24 September, just two days after completing work on Ocho comedias, it finished the printing of the Sermones, a work of almost double the size in the same quarto format, the privilegio of which had been granted just three months previously; and by 5 October it had managed to produce the twenty-five sheets of octavo of the Rhetoricae Compendium, having only started work after 12 September. These are impressive rates of productivity for three books that were printed concurrently, and are an indication that the Medina shop probably had four presses at its disposal. It may also have been able to distribute work to other shops, for, as Moll points out, this often happened when a book needed to be produced quickly, as, for example, in the case of the second Madrid edition of the first part of Don Quijote.69 Time was certainly of the essence where Ocho comedias was concerned, for Cervantes must have been anxious to see his plays printed before he died, and one imagines he would have conveyed his concerns to both Villarroel and Francisca Medina.

While Ocho comedias and the second part of the Quijote were at the printers, Cervantes was working hard to complete Persiles. He had long been aware that printers in Madrid worked on many jobs at the same time, with the result that authors could experience lengthy delays in the printing of their works, and had therefore developed his own method of concurrent production, which proved to be particularly important in preserving his plays for posterity. For much of his life he had felt ambivalent about print, and with good reason, for it had made him little money and had exposed him both to ridicule and literary piracy. Now, however, with his health failing, he worked feverishly to ensure that as much of his work as possible would be passed on to future generations. The printed book, whatever its shortcomings, was the storage medium that would ensure that his writing survived. The dedication to Don Pedro Fernández de Castro, Count of Lemos, dated 19 April 1616, just three days before his death, is a moving testament to his determination to keep writing as long as he still has the strength to hold his pen:

I still retain in my soul the vestiges and traces of Weeks in the Garden and the famous Bernardo. If, by chance, by good fortune (though it would not be fortune, but a miracle), heaven allows me to live, you will see them, and also the final part of Galatea.70

In presenting his last work, Cervantes, who knows he is dying, also offers his patron and his readers, present and future, the ghosts of unfinished projects, those that neither the print-shop nor the wider world would ever see.

Notes

1 Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, Ocho comedias, y ocho entremeses nuevos, Nunca representados (Madrid: La viuda de Alonso Martín, 1615). In references to early editions, including titles and quotations, spelling, punctuation, capitalization, and accentuation is reproduced as found in the source consulted, with the following exceptions, all of which have been regularized: the long ‘s’; where ‘u’ stands for ‘v’ (e.g. ‘auenturas’) and vice-versa (e.g. ‘Don Qvixote’); and where ‘i’ stands for ‘j’ (e.g. ‘trabaios’).

2 ‘No hallé autor que me las pidiese, puesto que sabían que las tenía; y así las arrinconé en un cofre y las consagré y condené al perpetuo silencio. En esta sazón me dijo un librero que él me las comprara si un autor de título no le hubiera dicho que de mi prosa se podía esperar mucho, pero que del verso nada.’ La entretenida, ed. by John O’Neill (London: King’s College, 2014), published online at http://entretenida.outofthewings.org. All translations are my own.

3 Jonathan Thacker, A Companion to Golden Age Theatre (Woodbridge: Tamesis, 2007), p. 59. Miguel Cervantes, Pedro, The Great Pretender, trans. by Philip Osment (London: Oberon Books, 2004).

4 Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, Segunda parte del ingenioso cavallero Don Quixote de la Mancha (Madrid: Juan de la Cuesta, 1615 ).

5 Fermín de los Reyes Gómez, ‘La censura del libro: legislación y consecuencias. La impresión del Quijote’, in Imprenta, libros y lectura en la España del Quijote, ed. by José Manuel Lucía Megías (Madrid: Imprenta Artesanal, 2006), pp. 159—80 (p. 163).

6 Gómez, ‘La censura del libro’, p. 165.

7 ibid. pp. 164—65.

8 Cervantes, Segunda parte, fols. [ii]r—[v]v.

9 When Cuesta joined the printing-house of Pedro Madrigal in 1599, it was jointly owned by Madrigal’s widow María Rodríguez de Ribalde (who had married Juan Iñiguez de Lequerica, and been widowed again), and their son, also called Pedro Madrigal. In 1604, after the younger Pedro died, his widow, María Quiñones, married Cuesta, who took over the running of the shop. Books produced there continued to bear his name until Ribalde’s death in 1626, even though Cuesta moved to Sevilla in 1607, abandoning his pregnant wife. Juan Delgado Casado, Diccionario de impresores españoles (siglos XV—XVII), 2 vols (Madrid: Arco/Libros, 1996), I, 175; Jaime Moll, ‘Juan de la Cuesta’, in Gran enciclopedia cervantina, ed. by Carlos Alvar, 10 vols (Madrid: Castalia, 2005— ), III(2006), 3020.[Note from Spanish Classic Books: more correct information at this link]

10 Cervantes, Ocho comedias, fol. [ii]r.

11 D. F. McKenzie, ‘Printers of the Mind: Some Notes on Bibliographical Theories and Printing-House Practices’, in Making Meaning: ‘Printers of the Mind’ and Other Essays, ed. by Peter D. McDonald and Michael Felix Suarez (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2002), pp. 13—85.

12 Miguel de Cervantes, Primera parte de La Galatea, dividida en seys libros (Alcalá: Juan Gracián, 1585).

13 The other six editions were produced in Lisbon (1590), Paris (1611), Baeza (1617), Valladolid (1617), Lisbon (1618), and Barcelona (1618). See La Galatea, ed. by Francisco López Estrada and María Teresa López García-Berdoy (Madrid: Cátedra, 1999), pp. 124—25.

14 ‘Que alguno dellos tiene casi de memoria, la primera parte desta’; Don Quijote de La Mancha, ed. by the Instituto Cervantes, dir. by Francisco Rico (Barcelona: Galaxia Gutenberg/Círculo de Lectores; Centro para la Edición de los Clásicos Españoles, 2004), I, 669. References to this edition are by part, chapter (where applicable), and page.

15 ‘Aquesta es La Galatea | que, si buen libro desea | no tiene más que pedir’; cited in La Galatea, ed. Estrada & García-Berdoy, p. 99.

16 Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha (Madrid: Juan de la Cuesta, 1605). For the quotation see Don Quijote, I, Prólogo; ed. Instituto Cervantes, p. 11. Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, Novelas exemplares (Madrid: Juan de la Cuesta, 1613).

17 Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, Viage del Parnaso (Madrid: La viuda de Alonso Martín, 1614); Los trabajos de Persiles, y Sigismunda, historia Setentrional (Madrid: Juan de la Cuesta, 1617).

18 Don Quijote, II. 62; ed. Instituto Cervantes, pp. 1247—51.

19 ‘—Pues ¿qué? —dijo el autor—. ^Quiere vuesa merced que se lo dé a un librero que me dé por el privilegio tres maravedís, y aun piensa que me hace merced en dármelos?’; Don Quijote, II. 62; ed. Instituto Cervantes, p. 1250. The basic units of currency when Cervantes was writing were the copper maravedí, the silver real (royal), equivalent to 34 maravedís, and the gold escudo (shield), the value of which fluctuated, from 350 maravedíswhen it was introduced in 1535, to 400 maravedís in 1566, to 440 maravedís in 1609. The gold ducado, worth 375 maravedís or 11 reales, was an older coin, which was replaced by the escudo during the reign of Charles V, but still functioned as a unit of account in Cervantes’s time. See Bernat Hernández, ‘Monedas, pesos y medidas’, in Don Quijote, ed. Instituto Cervantes, pp. 941—47 (pp. 941—42)

20 ‘-No daré el privilegio de este mi libro a ningún librero de Madrid, si me da por él dos mil ducados; que allí no hay ninguno que no quiera los privilegios de balde, o, a lo menos, por tan poco precio que no le luzga al autor del libro’; Los trabajos de Persiles y Sigismunda, ed. by Carlos Romero Muñoz (Madrid: Cátedra, 2002), p. 635.

21 Krzysztof Sliwa, ‘Documentación’, in Gran enciclopedia cervantina,IV (2007), 3570—3646 (p22p. 3589—90).

22 Gómez, ‘La censura del libro’, p. 171.

23 Cristobál Pérez Pastor, Bibliografía madrileña, ó descripción de las obras impresas en Madrid, 3 vols (Madrid: Tipografía de los Huérfanos/Tipografía de la Revista de Archivos, Bibliotecas y Museos, 1891—1907), II, 250.

24 Don Quijote, II, ed. Instituto Cervantes, p. 670.

25 Don Quijote, II, ed. Instituto Cervantes, p. 679.

26 ‘Bien sé lo que son tentaciones del demonio, y que una de las mayores es ponerle a un hombre en el entendimiento que puede componer y imprimir un libro con que gane tanta fama como dineros y tantos dineros cuanta fama.’ Don Quijote, II, ed. Instituto Cervantes, p. 675.

27 ‘Yo no imprimo mis libros para alcanzar fama en el mundo, que ya en él soy conocido por mis obras: provecho quiero, que sin él no vale un cuatrín la buena fama.’ Don Quijote, II. 62; ed. Instituto Cervantes, p. 1250.

28 Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda, Segundo tomo del ingenioso hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha, que contiene su tercera salida : y es la quinta parte de sus aventuras (Tarragona: Felipe Roberto, 1614).

29 Don Quijote, II. 62; ed. Instituto Cervantes, p. 1251.

30 ‘Iten, suplico a los dichos señores mis albaceas que si la buena suerte les trujere a conocer al autor que dicen que compuso una historia que anda por ahí con el título de Segunda parte de las hazañas de don Quijote de la Mancha, de mi parte le pidan, cuan encarecidamente ser pueda, perdone la ocasión que sin yo pensarlo le di de haber escrito tantos y tan grandes disparates como en ella escribe, porque parto desta vida con escrúpulo de haberle dado motivo para escribirlos’; Don Quijote, II. 74; ed. Instituto Cervantes, p. 1334.

31 ‘Muchas veces acontece que los que tenían méritamente granjeada y alcanzada gran fama por sus escritos, en dándolos a la estampa la perdieron del todo o la menoscabaron en algo. —La causa deso es —dijo Sansón— que, como las obras impresas se miran despacio, fácilmente se veen sus faltas, y tanto más se escudriñan cuanto es mayor la fama del que las compuso’; Don Quijote, II. 3; ed. Instituto Cervantes, p. 713.

32 ‘Pero yo pienso darlas a la estampa, para que se vea despacio lo que pasa apriesa, y se disimula, o no se entiende cuando las representan. Y las comedias tienen sus sazones y tiempos, como los cantares.’ Viaje del Parnaso, ed. by Miguel Herrero García (Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Instituto Miguel de Cervantes, 1983), p. 314.

33 El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha, 2nd edn (Madrid: Juan de la Cuesta, 1605). The six occasions on which reference is made to the donkey can be found on fols. 109r, IIIV, 112r, 120V; 121r and 122r.

34 El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha (Brussels: Roger Velpius, 1607). The six corrections are located on fols. 210r, 215r, 216r, 232r, 233r and 235r. El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha (Madrid: Juan de la Cuesta, 1608). The two corrections can be found on fols. 96r and 98v.

35 ‘—No está en eso el yerro —replicó Sansón—, sino en que antes de haber parecido el jumento dice el autor que iba a caballo Sancho en el mesmo rucio. —A eso —dijo Sancho— no sé qué responder, sino que el historiador se engañó, o ya sería descuido del impresor.’ Don Quijote, II. 4; ed. Instituto Cervantes, p. 716.

36 ‘Dezidnos della, que ay hombre | que hasta de una mula parda | saber el sucesso aguarda, | la color, el talle, y nombre: | O si no dirán que fue | olvido del escritor’. Lope de Vega Carpio, Ventidos parte perfeta de las comedias(Madrid: La viuda de Juan Gonzalez, 1635), fol. 166r.

37 Roger Chartier, Inscription and Erasure: Literature and Written Culture from the Eleventh to the Eighteenth Century (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007), p. 34.

38 Miguel de Cervantes, ed. by Jorge García López, Novelas ejemplares (Barcelona: Circulo de Lectores/Galaxia Gutenberg, 2005), p. 16.

39 Novelas ejemplares, ed. García López, pp. 19—20.

40 ‘Don Quijote de la Mancha queda calzadas las espuelas en su segunda parte, para ir a besar los pies a V. E. […] Luego irá el gran Persiles, y luego Las semanas del jardín, y luego la segunda parte de La Galatea’; La entretenida,ed. O’Neill.

41 See Don Quijote, II; ed. Instituto Cervantes, pp. 677 and 679, and Persiles, ed. Romero Muñoz, pp. 117—18.

42 The title of Bernardo could be a reference to the legendary Spanish hero Bernardo del Carpio, who appears as a character in Cervantes’s play La casa de los celos, and is mentioned in El gallardo español and (several times) in Don Quijote.

43 The preliminares of Avellaneda’s Quijote do not include a privilegio, fe de erratas or tasa. The last date in the front matter is 4 July, which is when the second aprobacián was signed (fol. [ii]r). It is unlikely that a work of this size (sixty-eight sheets of quarto) could have been printed in less than two months, so the earliest date that it could have been published is September, which is the date that Canavaggio gives (Don Quijote, ed. Instituto Cervantes, p. CCCI). However, it is difficult to imagine that Cervantes, had he known about Avellaneda’s Quijote,would not have found a way of inserting some reference to it in the preliminares to Viaje del Parnaso, just as he did in the dedication to Ocho comedias and the prologue to the second part of Don Quijote. Such a reference could even have been added after the fe de erratas (11 November) and tasa (17 November), as was the case with the dedication of the Segunda parte. It therefore seems unlikely that Cervantes found out about Avellaneda’s Quijote until late November or December 1614.

44 Since Cervantes mentions having only six plays and interludes ready for publication in the Adjunta al Parnaso(see Viaje del Parnaso, ed. Herrero García, p. 314), he probably wrote the new material in the period of approximately five months between finishing Don Quijote and handing over the manuscript of Ocho comedias to the printers.

45 Don Quijote, II. 62; ed. Instituto Cervantes, p. 1250.

46 ‘Sabemos por los contratos de impresión conservados que, por lo general, cuando se acordaba una edición, se exigía que no se aceptara otro trabajo hasta que se acabara el recién admitido, lo cual, descartando las salidas de la norma que hubiera, implicaba la organización de la empresa en torno a un proyecto, al margen de los pequeños encargos que se aceptaran’; Sonia Garza Merino, ‘La cuenta del original’, in Imprenta y crítica textual en el siglo de oro, ed. by Francisco Rico, Pablo Andrés, and Sonia Garza (Valladolid: Universidad de Valladolid, Centro para la Edición de los Clásicos Españoles, 2000), pp. 65—95 (p. 73).

47 Juan Vázquez de Mármol, Condiciones que se pueden poner cuando se da a imprimir un libro (Madrid: El Crotalón, 1983). The Condiciones are part of an autograph miscellany preserved at the Biblioteca Nacional de Madrid (sig. Mss/9226, fol. 243r—v).

48 ‘Que el impressor se obligue a començar a imprimirlo dentro de tanto tiempo y despues de comenzado no dexe de proseguir en el so cierta pena.’

49 Neither the Dictionarium nor El cavallero puntual required a privilegio, since they were new editions, so estimates have been provided. If the speed of printing of the Dictionarium matched that of the Historia general,which was 319 sheets of folio and in production for nine months, then this work, which was almost exactly two thirds as long at 213 sheets of folio, would have been in production for six months. If, on the other hand, one assumes that production was at the average rate of 4. 5 sheets a week for folio at the la Cuesta shop between 1612 and 1615, printing of the Dictionarium would not have started until late September 1614. The only other work in duodecimo format, apart from El cavallero puntual, produced by Juan de la Cuesta in the period in question was the 1614 edition of Jorge Manrique’s Coplas (see Pérez Pastor, Bibliografía madrileña, p. 297). The production window of that book, which comprised 17 sheets, spanned seven months, from 21 June 1613 until 17 January 1614. If the 13 sheets of El cavallero puntual were printed at a similar rate, production would have started sometime around the beginning of June 1615. However, none of these estimates should be regarded as reliable, since, as this study shows, it is very difficult to calculate rates of production for works that are printed concurrently.

50 McKenzie, ‘Printers of the Mind’, pp. 25—26.

51 El ingenioso hidalgo, fols. [ii]rand [iii]v.

52 Segunda parte, fols. [ii]rand [v]v.

53 Francisco Rico, El texto del ‘Quijote’: preliminares a una ecdótica del siglo de oro (Barcelona: Ediciones Destino, 2005), p. 210.

54 Jaime Moll, Problemas bibliográficos del libro del siglo de oro (Madrid: Arco/Libros, 2011), pp. 118—19.

55 Antonio de Herrera, Historia General de los Hechos de los Castellanos en las Islas y Tierra Firme del Mar Oceano [General History of the Deeds of the Castilian People in the Islands and Mainlands of the Oceans], pt. V—VIII, 2 vols (Madrid: Juan de la Cuesta, 1615); Antonio Nebrija, Dictionarium (repr. Madrid: Juan de la Cuesta, 1615); Francisco Murcia de la Llana, Compendio de los Metheoros del Principe de los Filosofos Griegos y Latinos Aristoteles[‘Compendium of the Meteorological Observations of the Prince of Greek and Latin Philosophers Aristoteles’] (Madrid: Juan de la Cuesta, 1615); Alonso Jerónimo de Salas Barbadillo, El Cavallero puntual, pt. 1, 2nd edn (Madrid: Juan de la Cuesta, 1615).

56 Segunda parte, fol. [ii]v.

57 Sermones predicados en la Beatificacion de La B. M. Teresa de Jesus Virgen (Madrid: La viuda de Alonso Martín, 1615); Rhetoricae Compendium ex scriptis Patris Ioannis Baptistae Poza (Madrid: La viuda de Alonso Martín, 1615); Alonso de Ledesma, Romancero y Monstro imaginado (Madrid: La viuda de Alonso Martín, 1615). A romancero is a collection of romances (ballads).

58 Philip Gaskell, A New Introduction to Bibliography (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972), p. 164.

59 ‘La práctica más común fue el reparto de la composición de un cuaderno entre cajistas que, trabajando sincronizadamente, fueran suministrando las formas a uno o dos tiradores diferentes, de manera que al cabo del día pudieran tener impreso un pliego, por lo menos, de una tirada corriente de mil o mil quinientos ejemplares’; Garza Merino, ‘La cuenta del original’, p. 73.

60 McKenzie ‘Printers of the Mind’, pp. 28—30.

61 Juan de Aranda, Lugares comunes de Conceptos, Dichos y Sentencias en diversas materias, 2nd edn (Madrid: Juan de La Cuesta, 1613); Gonzalo de Illescas, Segunda parte de la Historia Pontifical y Catholica (repr. Madrid: Juan de la Cuesta, 1613). See Pérez Pastor, Bibliografía madrileña, pp. 246—47, 26524.

62 Arithmetica Practica y Speculativa (Madrid: La viuda de Alonso Martín, 1615). Villaroel was granted a licencia on 4 December 1614 (see Pérez Pastor, Bibliografía madrileña, p. 351).

63 Historia etiopica de los amores de Teogenes y Cariclea (Madrid: La viuda de Alonso Martín, 1615). The licenciawas granted on 10 February 1615, and the last date in the front matter is 13 June, which is when the dedication was signed (see Pérez Pastor, Bibliografía madrileña, p. 334).

64 The only other work with which Villarroel was associated was Persiles y Sigismunda, but that was printed by Juan de la Cuesta, although Medina’s shop did produce an edition, in 1619 (see Pérez Pastor, Bibliografía madrileña, p. 481).

65 K. Sliwa, Documentos de Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (Pamplona: Ediciones Universidad de Navarra, S.A., 1999), p. 369.

66 ‘Él me las pagó razonablemente’; La entretenida, ed. O’Neill. Regarding the debt, see Sliwa, Documentos, pp. 371—72.

67 Jaime Moll, ‘Viuda de Alonso Martín’, in Gran Enciclopedia Cervantina, VIII (2011), p. 7639.

68 Lope de Vega, Sexta parte de sus Comedias (Madrid: la viuda de Alonso Martín, 1615). Other important works produced at the Medina shop included editions of Cervantes’s Novelas ejemplares (1622), Montemayor’s La Diana(1622), and Rojas’s Tragicomedia de Calisto y Melibea (1632).

69 Moll, Problemas bibliográficos, p. 120.

70 ‘Todavía me quedan en el alma ciertas reliquias y asomos de Las semanas del jardín, y del famoso Bernardo. Si, a dicha, por buena ventura mía (que ya no sería ventura, sino milagro), me diese el cielo vida, las verá, y, con ellas, fin de La Galatea’; Persiles y Sigismunda, ed. Romero Muñoz, pp. 117—18.

© The Author 2015; all rights reserved