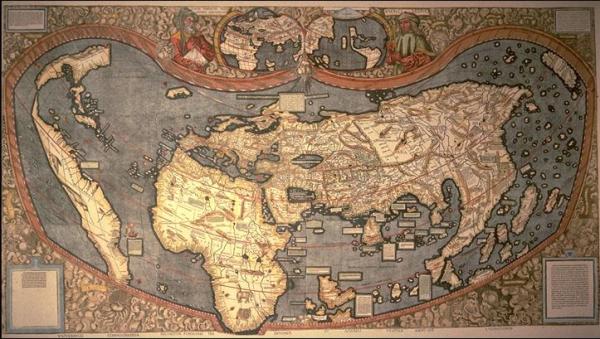

The portrait of the Spanish national character, in the context of the interrelations between Spaniards and foreigners in Europe, is presented by Cervantes in an exemplary novel set in Italy at some undetermined date in the last quarter of the 16th century: Lady Cornelia. In this short novel, there are most abundant considerations about their way of being, approached from a moral perspective as a catalog of virtues and vices.

In this magnificent novel the way of being attributed to the Spaniards plays a key role in the development of the plot. The true protagonist of the story we are told is Cornelia, a young Bolognese girl, beautiful, of noble lineage and orphan of father and mother; but two Spanish gentlemen, of Biscayan origin and friends, Don Juan de Gamboa and Don Antonio de Isunza, who abandon their studies in Salamanca to go to Flanders, also play a very important role, but, things being peaceful here, they decide to undertake a journey through Italy, after which they settle in Bologna to continue their studies in the famous College of the Spaniards of the University of Bologna. Shortly after the novel begins, the narrator portrays the two young Spanish noblemen as well-bred, gentle, discreet, courageous, restrained and liberal men. They are the prototype of the Spanish gentleman. Well, the Italians with whom they interact do not limit themselves to agreeing with the narrator in this portrait of them, but go a step further and elevate it to the category of a portrait of the Spaniards in general or of the common Spaniards.

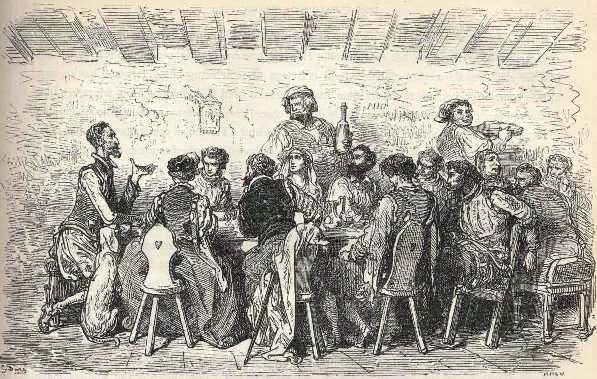

As if this were not enough, the two young Spanish gentlemen are free of a vice commonly attributed in Italy to Spaniards: that of arrogance or haughtiness. The author tells us that the two gentlemen friends led an intense social life in the university environment of Bologna, for they made many friends, not only among the Spanish students, but also among the Bolognese and foreigners.

Arrogance, however, plays no role in La señora Cornelia, precisely because the two Biscayan gentlemen, aware of the reputation that Spaniards have in Italy as arrogant, make every effort not to do anything that could be interpreted by their friends, acquaintances and other Italians with whom they have dealings as a sign of arrogance. Therefore, apart from this mention of this vice as typical of the Spaniards, there is no place in this novel for their defects, but only for their virtues, which play a key role in the development and happy outcome of Cornelia’s story. For it is the virtues of both gentlemen that lead them to become fully engaged in Cornelia’s story, which involves, apart from her and her newborn son, her beloved the Duke of Ferrara, Alfonso d’Este, and his brother Lorenzo, who mistakenly believes that his sister has been deceived and dishonored by the Duke and for which he hopes that the latter will give him satisfaction, either by marrying his sister or by fighting a duel with him.

It is Don Juan’s good qualities, especially his courage and generosity, that lead him to become involved in the story when, at the beginning of the narrative, he comes to the defense of the Duke, without knowing who he is, after seeing him attacked in an unequal manner by a group of six swordsmen, among whom is Don Lorenzo. Risking his life, he bravely enters the fight and saves the Duke’s life. This fact will contribute to make Don Juan an advocate and mediator between the Duke and Don Lorenzo. But it is not the nobleman of Ferrara who, although he is aware of Don Juan’s virtues, who interprets them as the virtues of this gentleman as a Spaniard. This role corresponds to Cornelia and her brother Lorenzo.

Unlike Don Juan, who enters the story of sickle and sickle on his own initiative, Don Antonio is drawn into it at the request of Cornelia, who, distressed and unhappy at having failed in her encounter with the Duke and fearing that her brother will commit some folly, thinking that the Duke has dishonored her and even that he will attempt against herself, she comes across Don Antonio, whom, after learning that he is a Spaniard, she appeals to his condition as such and to a virtue that she considers a national characteristic of Spaniards, courtesy, to obtain his protection.

Well, it is to this generous courtesy that Cornelia appeals to Don Antonio to help her remedy her ills. And Don Antonio, honoring his Spanish courtesy, one of whose main requirements is precisely to protect the ladies, immediately puts himself at the disposal of the Bolognese lady and takes her to the inn where the two Spanish gentlemen are staying during their stay in Bologna. There Cornelia will also meet Don Juan, from whom she will learn, thanks to the Duke’s hat that he is wearing after having given it to her as a trophy after the fight, that he knows the Duke, which causes the lady’s uneasiness, fearful that something bad might have happened to her beloved. However, she is somewhat reassured to know that he is in good hands, in the power of “gentle Spanish men”, otherwise the fear of losing his honesty would take his life. Again it is Spanish courtesy, for nothing else is gentleness, that offers security to the Italian lady.

Noting Cornelia’s signs of despondency and anxiety, notwithstanding her confession of trusting in Spanish gentleness, Don Juan, who speaks also for his friend, is obliged to reassure her with a few words in which he, after offering to serve her without hesitating to risk his life to defend and protect her, we are given a few hints about the moral character of the Spaniards, now seen from the perspective of a Spanish gentleman, who echoes, however, what Cornelia thinks of the goodness of the Spaniards

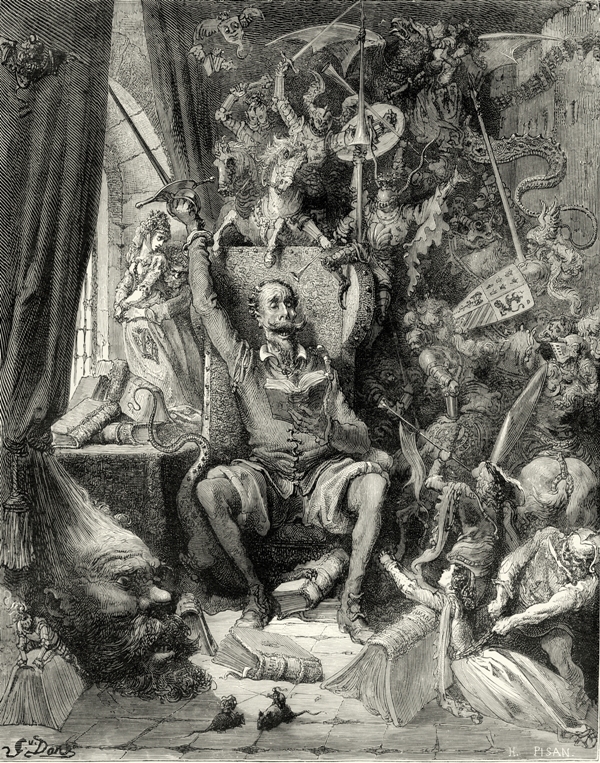

Cornelia supposes that the Spaniards are usually kind, which here is equivalent to generous. Don Juan, on behalf of himself and his friend, put themselves at the service of the lady to defend and protect her, but in saying of themselves that they, as Spaniards, are supposed to be good, he considers that this could be misinterpreted and understood to have crossed the limits of what a discreet and restrained gentleman should say and thus to have incurred in that arrogance attributed to the Spaniards in Italy from which they have so far tried to dissociate themselves. A gentleman must be humble and not speak of his virtues, for, as Don Quixote says, the praise of himself debases, although he himself does not apply this rule; it must be others who speak of them. For this reason, after presenting themselves as good before Cornelia, Don Juan hastens to clarify the matter by declaring that, although what he has said could be understood as arrogant on his part, in this case it is justified because the recognition of being good and principal is simply with the intention of reassuring a lady in distress and despondent, assuring her that she is in the hands of those who can be trusted to offer her shelter and protection.

Don Juan’s words have their effect and Cornelia reaffirms her decision to trust in the goodness or liberality of both Spanish gentlemen and tells them her story, in which the essential is that, in love with the Duke of Ferrara, after promising to be his wife, she gives herself to him and the fruit of this is a son, She meets him at the inn, where she was brought by Don Juan, who, on his first night outing through the streets of Bologna, before taking part in the quarrel between the Duke and his attackers, receives a newborn child as he passes through a door, which was not intended for him but for a servant of the Duke. Cornelia and her beloved had agreed that he would pick her up and take her to Ferrara to be publicly married, but she left her house before her suitor arrived and, frightened when she saw her brother’s armed gang, who would be the one to have the quarrel with the duke, and believing that her brother would use his sword against her, she left in panic until she ran into Don Antonio, thus frustrating the encounter with her beloved. But the most interesting thing, for our analysis, is that Cornelia, after having told what we have just summarized, finishes her touching relationship appealing again to the courtesy of the Spaniards, represented by the two Biscayan gentlemen, and in it she is confident to resolve her misfortunes favorably.

We have seen how the Basque gentlemen become fully immersed in the story through their main characters, Cornelia and the Duke of Ferrara. Well, also through a third important character, Don Lorenzo, Cornelia’s brother, they are even more immersed in the story, especially Don Juan. And the involvement of the latter through Don Lorenzo will allow the introduction of one more feature of the Spanish national character. If Cornelia’s lifeline is Spanish courtesy, her brother’s is Spanish courage. Indeed, Lorenzo, feeling aggrieved because he wrongly believes that the Duke has deceived and dishonored his sister, appears at the inn looking for Don Juan, whose help he requests to obtain from the Duke a satisfaction for his offense (that is, to accept to marry his sister) or, if he refuses, to arrange a duel, through which he has the opportunity to avenge the offense and defend his honor. And for this she needs the support of Don Juan, that he be her defender and mediator before the Duke, and she finds no better way to get it than asking him in the name of the proven courage of the Spaniards.

Perhaps the exaltation of the courage of the Spaniards with the example of Xerxes’ army is not very fortunate, considering that the Persian king was a loser and was defeated by the Greeks, but the intention is good, since Lorenzo only intends to enhance the courage and strength of the Spaniards. It is also interesting to note that Lorenzo’s request to Don Juan not only extols courage as a Spanish national trait, but also generosity. For in order to do what Lorenzo requests, although he requests it because of the confidence he has in the bravery of the Spaniards, it is not enough that the person requested be brave; it is also necessary that he be generously willing to help him by putting his courage at his service. Therefore, aware of this, and after accepting Don Juan’s request for Lorenzo’s help “because he is a Spaniard and a gentleman”, the Italian nobleman gratefully gives the Spaniard a hug and expressly acknowledges the latter’s generosity.

Don Juan will keep his word. He will meet with the Duke, who will confess that he has not deceived Cornelia, that he accepts her as his legitimate wife and also the child as his son, and that if so far he has not publicly married her it is because his mother wants to marry him to the daughter of the Duke of Mantua, but that, as soon as his mother dies, whose end seems imminent, he will marry her, which indeed will happen. So a story that seemed to dramatize a conflict of dishonor, of unfulfilled word, and of the consequent grievance, in the end harbors no more conflict than the postponement of the marriage until the opposition of the Duke’s mother ceases with her death. But the channelling of the story and its happy outcome has only been possible thanks to the intervention of two Spanish gentlemen who have acted as representatives of the best virtues attributed to the Spanish national character; two Biscayan gentlemen have been the best ambassadors or exponents of the Spanish genius in Italy.

Read it online in English below. In Spanish at this link.

Lady Cornelia

From The Exemplary Novels of Cervantes. Translated from the Spanish by Walter K. Kelly in 1881.

Don Antonio de Isunza and Don Juan de Gamboa, gentlemen of high birth and excellent sense, both of the same age, and very intimate friends, being students together at Salamanca, determined to abandon their studies and proceed to Flanders. To this resolution they were incited by the fervour of youth, their desire to see the world, and their conviction that the profession of arms, so becoming to all, is more particularly suitable to men of illustrious race.

But they did not reach Flanders until peace was restored, or at least on the point of being concluded; and at Antwerp they received letters from their parents, wherein the latter expressed the great displeasure caused them by their sons having left their studies without informing them of their intention, which if they had done, the proper measures might have been taken for their making the journey in a manner befitting their birth and station.

Unwilling to give further dissatisfaction to their parents, the young men resolved to return to Spain, the rather as there was now nothing to be done in Flanders. But before doing so they determined to visit all the most renowned cities of Italy; and having seen the greater part of them, they were so much attracted by the noble university of Bologna, that they resolved to remain there and complete the studies abandoned at Salamanca.

They imparted their intentions to their parents, who testified their entire approbation by the magnificence with which they provided their sons with every thing proper to their rank, to the end that, in their manner of living, they might show who they were, and of what house they were born. From the first day, therefore, that the young men visited the schools, all perceived them to be gallant, sensible, and well-bred gentlemen.

Don Antonio was at this time in his twenty-fourth year, and Don Juan had not passed his twenty-sixth. This fair period of life they adorned by various good qualities; they were handsome, brave, of good address, and well versed in music and poetry; in a word, they were endowed with such advantages as caused them to be much sought and greatly beloved by all who knew them. They soon had numerous friends, not only among the many Spaniards belonging to the university,[1]Cardinal Albornoz founded a college in the University of Bologna, expressly for the Spaniards, his countrymen. but also among people of the city, and of other nations, to all of whom they proved themselves courteous, liberal, and wholly free from that arrogance which is said to be too often exhibited by Spaniards.

Being young, and of joyous temperament, Don Juan and Don Antonio did not fail to give their attention to the beauties of the city. Many there were indeed in Bologna, both married and unmarried, remarkable as well for their virtues as their charms; but among them all there was none who surpassed the Signora Cornelia Bentivoglia, of that old and illustrious family of the Bentivogli, who were at one time lords of Bologna.

Cornelia was beautiful to a marvel; she had been left under the guardianship of her brother Lorenzo Bentivoglio, a brave and honourable gentleman. They were orphans, but inheritors of considerable wealth–and wealth is a great alleviation of the evils of the orphan state. Cornelia lived in complete seclusion, and her brother guarded her with unwearied solicitude. The lady neither showed herself on any occasion, nor would her brother consent that any one should see her; but this very fact inspired Don Juan and Don Antonio with the most lively desire to behold her face, were it only at church. Yet all the pains they took for that purpose proved vain, and the wishes they had felt on the subject gradually diminished, as the attempt appeared more and more hopeless. Thus, devoted to their studies, and varying these with such amusements as are permitted to their age, the young men passed a life as cheerful as it was honourable, rarely going out at night, but when they did so, it was always together and well armed.

One evening, however, when Don Juan was preparing to go out, Don Antonio expressed his desire to remain at home for a short time, to repeat certain orisons: but he requested Don Juan to go without him, and promised to follow him.

“Why should I go out to wait for you?” said Don Juan. “I will stay; if you do not go out at all to-night, it will be of very little consequence.” “By no means shall you stay,” returned Don Antonio: “go and take the air; I will be with you almost immediately, if you take the usual way.”

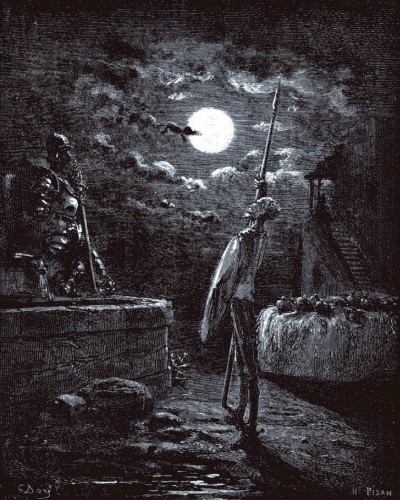

“Well, do as you please,” said Don Juan: “if you come you will find me on our usual beat.” With these words Don Juan left the house.

The night was dark, and the hour about eleven. Don Juan passed through two or three streets, but finding himself alone, and with no one to speak to, he determined to return home. He began to retrace his steps accordingly; and was passing through a street, the houses of which had marble porticoes, when he heard some one call out, “Hist! hist!” from one of the doors. The darkness of the night, and the shadow cast by the colonnade, did not permit him to see the whisperer; but he stopped at once, and listened attentively. He saw a door partially opened, approached it, and heard these words uttered in a low voice, “Is it you, Fabio?” Don Juan, on the spur of the moment, replied, “Yes!” “Take it, then,” returned the voice, “take it, and place it in security; but return instantly, for the matter presses.” Don Juan put out his hand in the dark, and encountered a packet. Proceeding to take hold of it, he found that it required both hands; instinctively he extended the second, but had scarcely done so before the portal was closed, and he found himself again alone in the street, loaded with, he knew not what.

Presently the cry of an infant, and, as it seemed, but newly born, smote his ears, filling him with confusion and amazement, for he knew not what next to do, or how to proceed in so strange a case. If he knocked at the door he was almost certain to endanger the mother of the infant; and if he left his burthen there, he must imperil the life of the babe itself. But if he took it home he should as little know what to do with it, nor was he acquainted with any one in the city to whom he could entrust the care of the child; yet remembering that he had been required to come back quickly, after placing his charge in safety, he determined to take the infant home, leave it in the hands of his old housekeeper, and return to see if his aid was needed in any way, since he perceived clearly that the person who had been expected to come for the child had not arrived, and the latter had been given to himself in mistake. With this determination, Don Juan soon reached his home; but found that Antonio had already left it. He then went to his chamber, and calling the housekeeper, uncovered the infant, which was one of the most beautiful ever seen; whilst, as the good woman remarked, the elegance of the clothes in which the little creature was wrapped, proved him–for it was a boy–to be the son of rich parents.

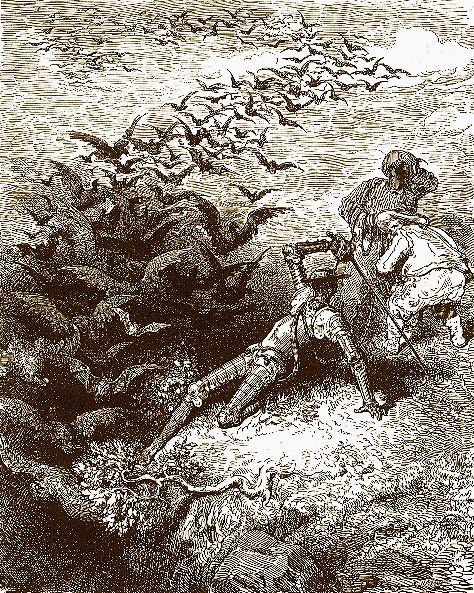

“You must, now,” said Don Juan to his housekeeper, “find some one to nurse this infant; but first of all take away these rich coverings, and put on him others of the plainest kind. Having done that, you must carry the babe, without a moment’s delay, to the house of a midwife, for there it is that you will be most likely to find all that is requisite in such a case. Take money to pay what may be needful, and give the child such parents as you please, for I desire to hide the truth, and not let the manner in which I became possessed of it be known.” The woman promised that she would obey him in every point; and Don Juan returned in all haste to the street, to see whether he should receive another mysterious call. But just before he arrived at the house whence the infant had been delivered to him, the clash of swords struck his ear, the sound being as that of several persons engaged in strife. He listened carefully, but could hear no word; the combat was carried on in total silence; but the sparks cast up by the swords as they struck against the stones, enabled him to perceive that one man was defending himself against several assailants; and he was confirmed in this belief by an exclamation which proceeded at length from the last person attacked. “Ah, traitors! you are many and I am but one, yet your baseness shall not avail you.”

Hearing and seeing this, Don Juan, listening only to the impulses of his brave heart, sprang to the side of the person assailed, and opposing the buckler he carried on his arm to the swords of the adversaries, drew his own, and speaking in Italian that he might not be known as a Spaniard, he said–“Fear not, Signor, help has arrived that will not fail you while life holds; lay on well, for traitors are worth but little however many there may be.” To this, one of the assailants made answer–“You lie; there are no traitors here. He who seeks to recover his lost honour is no traitor, and is permitted to avail himself of every advantage.”

No more was said on either side, for the impetuosity of the assailants, who, as Don Juan thought, amounted to not less than six, left no opportunity for further words. They pressed his companion, meanwhile, very closely; and two of them giving him each a thrust at the same time with the point of their swords, he fell to the earth. Don Juan believed they had killed him; he threw himself upon the adversaries, nevertheless, and with a shower of cuts and thrusts, dealt with extraordinary rapidity, caused them to give way for several paces. But all his efforts must needs have been vain for the defence of the fallen man, had not Fortune aided him, by making the neighbours come with lights to their windows and shout for the watch, whereupon the assailants ran off and left the street clear.

The fallen man was meanwhile beginning to move; for the strokes he had received, having encountered a breastplate as hard as adamant, had only stunned, but not wounded him.

Now, Don Juan’s hat had been knocked off in the fray, and thinking he had picked it up, he had in fact put on that of another person, without perceiving it to be other than his own. The gentleman whom he had assisted now approached Don Juan, and accosted him as follows:–“Signor Cavalier, whoever you may be, I confess that I owe you my life, and I am bound to employ it, with all I have or can command, in your service: do me the favour to tell me who you are, that I may know to whom my gratitude is due.”

“Signor,” replied Don Juan, “that I may not seem discourteous, and in compliance with your request, although I am wholly disinterested in what I have done, you shall know that I am a Spanish gentleman, and a student in this city; if you desire to hear my name I will tell you, rather lest you should have some future occasion for my services than for any other motive, that I am called Don Juan de Gamboa.”

“You have done me a singular service, Signor Don Juan de Gamboa,” replied the gentleman who had fallen, “but I will not tell you who I am, nor my name, which I desire that you should learn from others rather than from myself; yet I will take care that you be soon informed respecting these things.”

Don Juan then inquired of the stranger if he were wounded, observing, that he had seen him receive two furious lunges in the breast; but the other replied that he was unhurt; adding, that next to God, a famous plastron that he wore had defended him against the blows he had received, though his enemies would certainly have finished him had Don Juan not come to his aid.

While thus discoursing, they beheld a body of men advancing towards them; and Don Juan exclaimed–“If these are enemies, Signor, let us hasten to put ourselves on our guard, and use our hands as men of our condition should do.”

“They are not enemies, so far as I can judge,” replied the stranger. “The men who are now coming towards us are friends.”

And this was the truth; the persons approaching, of whom there were eight, surrounded the unknown cavalier, with whom they exchanged a few words, but in so low a tone that Don Juan could not hear the purport. The gentleman then turned to Don Juan and said–“If these friends had not arrived I should certainly not have left your company, Signor Don Juan, until you had seen me in some place of safety; but as things are, I beg you now, with all kindness, to retire and leave me in this place, where it is of great importance that I should remain.” Speaking thus, the stranger carried his hand to his head, but finding that he was without a hat, he turned towards the persons who had joined him, desiring them to give him one, and saying that his own had fallen. He had no sooner spoken than Don Juan presented him with that which he had himself just picked up, and which he had discovered to be not his own. The stranger having felt the hat, returned it to Don Juan, saying that it was not his, and adding, “On your life, Signor Don Juan, keep this hat as a trophy of this affray, for I believe it to be one that is not unknown.”

The persons around then gave the stranger another hat, and Don Juan, after exchanging a few brief compliments with his companion, left him, in compliance with his desire, without knowing who he was: he then returned home, not daring at that moment to approach the door whence he had received the newly-born infant, because the whole neighbourhood had been aroused, and was in movement.

Now it chanced that as Don Juan was returning to his abode, he met his comrade Don Antonio de Isunza; and the latter no sooner recognised him in the darkness, than he exclaimed, “Turn about, Don Juan, and walk with me to the end of the street; I have something to tell you, and as we go along will relate a story such as you have never heard before in your life.”

“I also have one of the same kind to tell you,” returned Don Juan, “but let us go up the street as you say, and do you first relate your story.” Don Antonio thereupon walked forward, and began as follows:–“You must know that in little less than an hour after you had left the house, I left it also, to go in search of you, but I had not gone thirty paces from this place when I saw before me a black mass, which I soon perceived to be a person advancing in great haste. As the figure approached nearer, I perceived it to be that of a woman, wrapped in a very wide mantle, and who, in a voice interrupted by sobs and sighs, addressed me thus, ‘Are you, sir, a stranger, or one of the city?’ ‘I am a stranger,’ I replied, ‘and a Spaniard.’ ‘Thanks be to God!’ she exclaimed, ‘he will not have me die without the sacraments.’ ‘Are you then wounded, madam?’ continued I, ‘or attacked by some mortal malady?’ ‘It may well happen that the malady from which I suffer may prove mortal, if I do not soon receive aid,’ returned the lady, ‘wherefore, by the courtesy which is ever found among those of your nation, I entreat you, Signor Spaniard, take me from these streets, and lead me to your dwelling with all the speed you may; there, if you wish it, you shall know the cause of my sufferings, and who I am, even though it should cost me my reputation to make myself known.’

“Hearing this,” continued Don Antonio, “and seeing that the lady was in a strait which permitted no delay, I said nothing more, but offering her my hand, I conducted her by the by-streets to our house. Our page, Santisteban, opened the door, but, commanding him to retire, I led the lady in without permitting him to see her, and took her into my room, where she had no sooner entered than she fell fainting on my bed. Approaching to assist her, I removed the mantle which had hitherto concealed her face, and discovered the most astonishing loveliness that human eyes ever beheld. She may be about eighteen years old, as I should suppose, but rather less than more. Bewildered for a moment at the sight of so much beauty, I remained as one stupified, but recollecting myself, I hastened to throw water on her face, and, with a pitiable sigh, she recovered consciousness.

“The first word she uttered was the question, ‘Do you know me, Signor?’ I replied, ‘No, lady! I have not been so fortunate as ever before to have seen so much beauty.’ ‘Unhappy is she,’ returned the lady, ‘to whom heaven has given it for her misfortune. But, Signor, this is not the time to praise my beauty, but to mourn my distress. By all that you most revere, I entreat you to leave me shut up here, and let no one behold me, while you return in all haste to the place where you found me, and see if there be any persons fighting there. Yet do not take part either with one side or the other. Only separate the combatants, for whatever injury may happen to either, must needs be to the increase of my own misfortunes.’ I then left her as she desired,” continued Don Antonio, “and am now going to put an end to any quarrel which may arise, as the lady has commanded me.”

“Have you anything more to say?” inquired Don Juan.

“Do you think I have not said enough,” answered Don Antonio, “since I have told you that I have now in my chamber, and hold under my key, the most wonderful beauty that human eyes have ever beheld.”

“The adventure is a strange one, without doubt,” replied Don Juan, “but listen to mine;” and he instantly related to his friend all that had happened to him. He told how the newly-born infant was then in their house, and in the care of their housekeeper, with the orders he had given as to changing its rich habits for others less remarkable, and for procuring a nurse from the nearest midwife, to meet the present necessity. “As to the combat you come in quest of,” he added, “that is already ended, and peace is made.” Don Juan further related that he had himself taken part in the strife; and concluded by remarking, that he believed those whom he had found engaged were all persons of high quality, as well as great courage.

Each of the Spaniards was much surprised at the adventure of the other, and they instantly returned to the house to see what the lady shut up there might require. On the way, Don Antonio told Don Juan that he had promised the unknown not to suffer any one to see her; assuring her that he only would enter the room, until she should herself permit the approach of others.

“I shall nevertheless do my best to see her,” replied Don Juan; “after what you have said of her beauty, I cannot but desire to do so, and shall contrive some means for effecting it.”

Saying this they arrived at their house, when one of their three pages, bringing lights, Don Antonio cast his eyes on the hat worn by Don Juan, and perceived that it was glittering with diamonds. Don Juan took it off, and then saw that the lustre of which his companion spoke, proceeded from a very rich band formed of large brilliants. In great surprise, the friends examined the ornament, and concluded that if all the diamonds were as precious as they appeared to be, the hat must be worth more than two thousand ducats. They thus became confirmed in the conviction entertained by Don Juan, that the persons engaged in the combat were of high quality, especially the gentleman whose part he had taken, and who, as he now recollected, when bidding him take the hat, and keep it, had remarked that it was not unknown.

The young men then commanded their pages to retire, and Don Antonio, opening the door of his room, found the lady seated on his bed, leaning her cheek on her hand, and weeping piteously. Don Juan also having approached the door, the splendour of the diamonds caught the eye of the weeping lady, and she exclaimed, “Enter, my lord duke, enter! Why afford me in such scanty measure the happiness of seeing you; enter at once, I beseech you.”

“Signora,” replied Don Antonio, “there is no duke here who is declining to see you.”

“How, no duke!” she exclaimed. “He whom I have just seen is the Duke of Ferrara; the rich decoration of his hat does not permit him to conceal himself.”

“Of a truth, Signora, he who wears the hat you speak of is no duke; and if you please to undeceive yourself by seeing that person, you have but to give your permission, and he shall enter.”

“Let him do so,” said the lady; “although, if he be not the duke, my misfortune will be all the greater.”

Don Juan had heard all this, and now finding that he was invited to enter, he walked into the apartment with his hat in his hand; but he had no sooner placed himself before the lady than she, seeing he was not the person she had supposed, began to exclaim, in a troubled voice and with broken words, “Ah! miserable creature that I am, tell me, Signor–tell me at once, without keeping me in suspense, what do you know of him who owned that sombrero? How is it that he no longer has it, and how did it come into your possession? Does he still live, or is this the token that he sends me of his death? Oh! my beloved, what misery is this! I see the jewels that were thine. I see myself shut up here without the light of thy presence. I am in the power of strangers; and if I did not know that they were Spaniards and gentlemen, the fear of that disgrace by which I am threatened would already have finished my life.”

“Calm yourself, madam,” replied Don Juan, “for the master of this sombrero is not dead, nor are you in a place where any increase to your misfortunes is to be dreaded. We think only of serving you, so far as our means will permit, even to the exposing our lives for your defence and succour. It would ill become us to suffer that the trust you have in the faith of Spaniards should be vain; and since we are Spaniards, and of good quality–for here that assertion, which might otherwise appear arrogant, becomes needful–be assured that you will receive all the respect which is your due.”

“I believe you,” replied the lady; “but, nevertheless, tell me, I pray you, how this rich sombrero came into your possession, and where is its owner? who is no less a personage than Alfonso d’Este, Duke of Ferrara.”

Then Don Juan, that he might not keep the lady longer in suspense, related to her how he had found the hat in the midst of a combat, in which he had taken the part of a gentleman, who, from what she had said, he could not now doubt to be the Duke of Ferrara. He further told her how, having lost his own hat in the strife, the gentleman had bidden him keep the one he had picked up, and which belonged, as he said, to a person not unknown; that neither the cavalier nor himself had received any wound; and that, finally, certain friends or servants of the former had arrived, when he who was now believed to be the duke had requested Don Juan to leave him in that place, where he desired for certain reasons to remain.

“This, madam,” concluded Don Juan, “is the whole history of the manner in which the hat came into my possession; and for its master, whom you suppose to be the Duke of Ferrara, it is not an hour since I left him in perfect safety. Let this true narration suffice to console you, since you are anxious to be assured that the Duke is unhurt.”

To this the lady made answer, “That you, gentlemen, may know how much reason I have to inquire for the duke, and whether I need be anxious for his safety, listen in your turn with attention, and I will relate what I know not yet if I must call my unhappy history.”

While these things were passing, the housekeeper of Don Antonio and Don Juan was occupied with the infant, whose mouth she had moistened with honey, and whose rich habits she was changing for clothes of a very humble character. When that was done, she was about to carry the babe to the house of the midwife, as Don Juan had recommended, but as she was passing with it before the door of the room wherein the lady was about to commence her history, the little creature began to cry aloud, insomuch that the lady heard it. She instantly rose to her feet, and set herself to listen, when the plaints of the infant arrived more distinctly to her ear.

“What child is this, gentlemen?” said she, “for it appears to be but just born.”

Don Juan replied, “It is a little fellow who has been laid at the door of our house to-night, and our servant is about to seek some one who will nurse it.”

“Let them bring it to me, for the love of God!” exclaimed the lady, “for I will offer that charity to the child of others, since it has not pleased Heaven that I should be permitted to nourish my own.”

Don Juan then called the housekeeper, and taking the infant from her arms he placed it in those of the lady, saying, “Behold, madam, this is the present that has been made to us to-night, and it is not the first of the kind that we have received, since but few months pass wherein we do not find such God-sends hooked on to the hinges of our doors.”

The lady had meanwhile taken the infant into her arms, and looked attentively at its face, but remarking the poverty of its clothing, which was, nevertheless, extremely clean, she could not restrain her tears. She cast the kerchief which she had worn around her head over her bosom, that she might succour the infant with decency, and bending her face over that of the child, she remained long without raising her head, while her eyes rained torrents of tears on the little creature she was nursing.

The babe was eager to be fed, but finding that it could not obtain the nourishment it sought, the lady returned the babe to Don Juan, saying, “I have vainly desired to be charitable to this deserted infant, and have but shown that I am new to such matters. Let your servants put a little honey on the lips of the child, but do not suffer them to carry it through the streets at such an hour; bid them wait until the day breaks, and let the babe be once more brought to me before they take it away, for I find a great consolation in the sight of it.”

Don Juan then restored the infant to the housekeeper, bidding her take the best care she could of it until daybreak, commanding that the rich clothes it had first worn should be put on it again, and directing her not to take it from the house until he had seen it once more. That done, he returned to the room; and the two friends being again alone with the beautiful lady, she said, “If you desire that I should relate my story, you must first give me something that may restore my strength, for I feel in much need of it.” Don Antonio flew to the beaufet for some conserves, of which the lady ate a little; and having drunk a glass of water, and feeling somewhat refreshed, she said, “Sit down, Signors, and listen to my story.”

The gentlemen seated themselves accordingly, and she, arranging herself on the bed, and covering her person with the folds of her mantle, suffered the veil which she had kept about her head to fall on her shoulders, thus giving her face to view, and exhibiting in it a lustre equal to that of the moon, rather of the sun itself, when displayed in all its splendour. Liquid pearls fell from her eyes, which she endeavoured to dry with a kerchief of extraordinary delicacy, and with hands so white that he must have had much judgment in colour who could have found a difference between them and the cambric. Finally, after many a sigh and many an effort to calm herself, with a feeble and trembling voice, she said–

“I, Signors, am she of whom you have doubtless heard mention in this city, since, such as it is, there are few tongues that do not publish the fame of my beauty. I am Cornelia Bentivoglio, sister of Lorenzo Bentivoglio; and, in saying this, I have perhaps affirmed two acknowledged truths,–the one my nobility, and the other my beauty. At a very early age I was left an orphan to the care of my brother, who was most sedulous in watching over me, even from my childhood, although he reposed more confidence in my sentiments of honour than in the guards he had placed around me. In short, kept thus between walls and in perfect solitude, having no other company than that of my attendants, I grew to womanhood, and with me grew the reputation of my loveliness, bruited abroad by the servants of my house, and by such as had been admitted to my privacy, as also by a portrait which my brother had caused to be taken by a famous painter, to the end, as he said, that the world might not be wholly deprived of my features, in the event of my being early summoned by Heaven to a better life.

“All this might have ended well, had it not chanced that the Duke of Ferrara consented to act as sponsor at the nuptials of one of my cousins; when my brother permitted me to be present at the ceremony, that we might do the greater honour to our kinswoman. There I saw and was seen; there, as I believe, hearts were subjugated, and the will of the beholders rendered subservient; there I felt the pleasure received from praise, even when bestowed by flattering tongues; and, finally, I there beheld the duke, and was seen by him; in a word, it is in consequence of this meeting that you see me here.

“I will not relate to you, Signors (for that would needlessly protract my story), the various stratagems and contrivances by which the duke and myself, at the end of two years, were at length enabled to bring about that union, our desire for which had received birth at those nuptials. Neither guards, nor seclusion, nor remonstrances, nor human diligence of any kind, sufficed to prevent it, and we were finally made one; for without the sanction due to my honour, Alfonso would certainly not have prevailed. I would fain have had him publicly demand my hand from my brother, who would not have refused it; nor would the duke have had to excuse himself before the world as to any inequality in our marriage, since the race of the Bentivogli is in no manner inferior to that of Este; but the reasons which he gave for not doing as I wished appeared to me sufficient, and I suffered them to prevail.

“The visits of the duke were made through the intervention of a servant, over whom his gifts had more influence than was consistent with the confidence reposed in her by my brother. After a time I perceived that I was about to become a mother, and feigning illness and low spirits, I prevailed on Lorenzo to permit me to visit the cousin at whose marriage it was that I first saw the duke; I then apprised the latter of my situation, letting him also know the danger in which my life was placed from that suspicion of the truth which I could not but fear that Lorenzo must eventually entertain.

“It was then agreed between us, that when the time for my travail drew near, the duke should come, with certain of his friends, and take me to Ferrara, where our marriage should be publicly celebrated. This was the night on which I was to have departed, and I was waiting the arrival of Alfonso, when I heard my brother pass the door with several other persons, all armed, as I could hear, by the noise of their weapons. The terror caused by this event was such as to occasion the premature birth of my infant, a son, whom the waiting-woman, my confidant, who had made all ready for his reception, wrapped at once in the clothes we had provided, and gave at the street-door, as she told me, to a servant of the duke. Soon afterwards, taking such measures as I could under circumstances so pressing, and hastened by the fear of my brother, I also left the house, hoping to find the duke awaiting me in the street. I ought not to have gone forth until he had come to the door; but the armed band of my brother, whose sword I felt at my throat, had caused me such terror that I was not in a state to reflect. Almost out of my senses I came forth, as you behold me; and what has since happened you know. I am here, it is true, without my husband, and without my son; yet I return thanks to Heaven which has led me into your hands–for from you I promise myself all that may be expected from Spanish courtesy, reinforced, as it cannot but be in your persons, by the nobility of your race.”

Having said this, the lady fell back on the bed, and the two friends hastened to her assistance, fearing she had again fainted. But they found this not to be the case; she was only weeping bitterly. Wherefore Don Juan said to her, “If up to the present moment, beautiful lady, my companion Don Antonio, and I, have felt pity and regret for you as being a woman, still more shall we now do so, knowing your quality; since compassion and grief are changed into the positive obligation and duty of serving and aiding you. Take courage, and do not be dismayed; for little as you are formed to endure such trials, so much the more will you prove yourself to be the exalted person you are, as your patience and fortitude enable you to rise above your sorrows. Believe me, Signora, I am persuaded that these extraordinary events are about to have a fortunate conclusion; for Heaven can never permit so much beauty to endure permanent sorrow, nor suffer your chaste purposes to be frustrated. Go now to bed, Signora, and take that care of your health of which you have so much need; there shall presently come to wait on you a servant of ours, in whom you may confide as in ourselves, for she will maintain silence respecting your misfortunes with no less discretion than she will attend to all your necessities.”

“The condition in which I find myself,” replied the lady, “might compel me to the adoption of more difficult measures than those you advise. Let this woman come, Signors; presented to me by you, she cannot fail to be good and serviceable; but I beseech you let no other living being see me.”

“So shall it be,” replied Don Antonio; and the two friends withdrew, leaving Cornelia alone.

Don Juan then commanded the housekeeper to enter the room, taking with her the infant, whose rich habits she had already replaced. The woman did as she was ordered, having been previously told what she should reply to the questions of the Signora respecting the infant she bore in her arms Seeing her come in, Cornelia instantly said, “You come in good time, my friend; give me that infant, and place the light near me.”

The servant obeyed; and, taking the babe in her arms, Cornelia instantly began to tremble, gazed at him intently, and cried out in haste, “Tell me, good woman, is this child the same that you brought me a short time since?” “It is the same, Signora,” replied the woman. “How is it, then, that his clothing is so different? Certainly, dame housekeeper, either these are other wrappings, or the infant is not the same.” “It may all be as you say,” began the old woman. “All as I say!” interrupted Cornelia, “how and what is this? I conjure you, friend, by all you most value, to tell me whence you received these rich clothes; for my heart seems to be bursting in my bosom! Tell me the cause of this change; for you must know that these things belong to me, if my sight do not deceive me, and my memory have not failed. In these robes, or some like them, I entrusted to a servant of mine the treasured jewel of my soul! Who has taken them from him? Ah, miserable creature that I am! who has brought these things here? Oh, unhappy and woeful day!”

Don Juan and Don Antonio, who were listening to all this, could not suffer the matter to go further, nor would they permit the exchange of the infant’s dress to trouble the poor lady any longer. They therefore entered the room, and Don Juan said, “This infant and its wrappings are yours, Signora;” and immediately he related from point to point how the matter had happened. He told Cornelia that he was himself the person to whom the waiting woman had given the child, and how he had brought it home, with the orders he had given to the housekeeper respecting its change of clothes, and his motives for doing so. He added that, from the moment when she had spoken of her own infant, he had felt certain that this was no other than her son; and if he had not told her so at once, that was because he feared the effects of too much gladness, coming immediately after the heavy grief which her trials had caused her.

The tears of joy then shed by Cornelia were many and long-continued; infinite were the acknowledgments she offered to Heaven, innumerable the kisses she lavished on her son, and profuse the thanks which she offered from her heart to the two friends, whom she called her guardian angels on earth, with other names, which gave abundant proof of her gratitude. They soon afterwards left the lady with their housekeeper, whom they enjoined to attend her well, and do her all the service possible–having made known to the woman the position in which Cornelia found herself, to the end that she might take all necessary precautions, the nature of which, she, being a woman, would know much better than they could do. They then went to rest for the little that remained of the night, intending to enter Cornelia’s apartment no more, unless summoned by herself, or called thither by some pressing need.

The day having dawned, the housekeeper went to fetch a woman, who agreed to nurse the infant in silence and secrecy. Some hours later the friends inquired for Cornelia, and their servant told them that she had rested a little. Don Juan and Don Antonio then went to the Schools. As they passed by the street where the combat had taken place, and near the house whence Cornelia had fled, they took care to observe whether any signs of disorder were apparent, and whether the matter seemed to be talked of in the neighbourhood: but they could hear not a word respecting the affray of the previous night, or the absence of Cornelia. So, having duly attended the various lectures, they returned to their dwelling.

The lady then caused them to be summoned to her chamber; but finding that, from respect to her presence, they hesitated to appear, she replied to the message they sent her, with tears in her eyes, begging them to come and see her, which she declared to be now the best proof of their respect as well as interest; since, if they could not remedy, they might at least console her misfortunes.

Thus exhorted, the gentlemen obeyed, and Cornelia received them with a smiling face and great cordiality. She then entreated that they would do her the kindness to walk about the city, and ascertain if anything had transpired concerning her affairs. They replied, that they had already done so, with all possible care, but that not a word had been said reacting the matter.

At this moment, one of the three pages who served the gentlemen approached the door of the room telling his masters from without, that there was then at the street door, attended by two servants, a gentleman, who called himself Lorenzo Bentivoglio, and inquired for the Signor Don Juan de Gamboa. Hearing this message, Cornelia clasped her hands, and placing them on her mouth, she exclaimed, in a low and trembling voice, while her words came with difficulty through those clenched fingers, “It is my brother, Signors! it is my brother! Without doubt he has learned that I am here, and has come to take my life. Help and aid, Signors! help and aid!”

“Calm yourself, lady,” replied Don Antonio; “you are in a place of safety, and with people who will not suffer the smallest injury to be offered you. The Signor Don Juan will go to inquire what this gentleman demands, and I will remain to defend you, if need be, from all disturbance.”

Don Juan prepared to descend accordingly, and Don Antonio, taking his loaded pistols, bade the pages belt on their swords, and hold themselves in readiness for whatever might happen. The housekeeper, seeing these preparations began to tremble,–Cornelia, dreading some fearful result was in grievous terror,–Don Juan and Don Antonio alone preserved their coolness.

Arrived at the door of the house, Don Juan found Don Lorenzo, who, coming towards him, said, “I entreat your Lordship”–for such is the form of address among Italians–“I entreat your Lordship to do me the kindness to accompany me to the neighbouring church; I have to speak to you respecting an affair which concerns my life and honour.”

“Very willingly,” replied Don Juan. “Let us go, Signor, wherever you please.”

They walked side by side to the church, where they seated themselves on a retired bench, so as not to be overheard. Don Lorenzo was the first to break silence.

“Signor Spaniard,” he said, “I am Lorenzo Bentivoglio; if not of the richest, yet of one of the most important families belonging to this city; and if this seem like boasting of myself, the notoriety of the fact may serve as my excuse for naming it. I was left an orphan many years since, and to my guardianship was left a sister, so beautiful, that if she were not nearly connected with me, I might perhaps describe her in terms that, while they might seem exaggerated, would yet not by any means do justice to her attractions. My honour being very dear to me, and she being very young, as well as beautiful, I took all possible care to guard her at all points; but my best precautions have proved vain; the self-will of Cornelia, for that is her name, has rendered all useless. In a word, and not to weary you–for this story might become a long one,–I will but tell you, that the Duke of Ferrara, Alfonso d’Este, vanquishing the eyes of Argus by those of a lynx, has rendered all my cares vain, by carrying off my sister last night from the house of one of our kindred; and it is even said that she has already become a mother.

“The misfortune of our house was made known to me last night, and I instantly placed myself on the watch; nay, I met and even attacked Alfonso, sword in hand; but he was succoured in good time by some angel, who would not permit me to efface in his blood the stain he has put upon me. My relation has told me, (and it is from her I have heard all,) that the duke deluded my sister, under a promise to make her his wife; but this I do not believe, for, in respect to present station and wealth, the marriage would not be equal, although, in point of blood, all the world knows how noble are the Bentivogli of Bologna. What I fear is, that the duke has done, what is but too easy when a great and powerful Prince desires to win a timid and retiring girl: he has merely called her by the tender name of wife, and made her believe that certain considerations have prevented him from marrying her at once,–a plausible pretence, but false and perfidious.

“Be that as it may, I see myself at once deprived of my sister and my honour. Up to this moment I have kept the matter secret, purposing not to make known the outrage to any one, until I see whether there may not be some remedy, or means of satisfaction to be obtained. It is better that a disgrace of this kind be supposed and suspected, than certainly and distinctly known–seeing that between the yes and the no of a doubt, each inclines to the opinion that most attracts him, and both sides of the question find defenders. Considering all these things, I have determined to repair to Ferrara, and there demand satisfaction from the duke himself. If he refuse it, I will then offer him defiance. Yet my defiance cannot be made with armed bands, for I could neither get them together nor maintain them but as from man to man. For this it is, then, that I desire your aid. I hope you will accompany me in the journey; nay, I am confident that you will do so, being a Spaniard and a gentleman, as I am told you are.

“I cannot entrust my purpose to any relation or friend of my family, knowing well that from them I should have nothing more than objections and remonstrances, while from you I may hope for sensible and honourable counsels, even though there should be peril in pursuing them. You must do me the favour to go with me, Signor. Having a Spaniard, and such as you appear to be, at my side, I shall account myself to have the armies of Xerxes. I am asking much at your hands; but the duty of answering worthily to what fame publishes of your nation, would oblige you to do still more than I ask.”

“No more, Signor Lorenzo,” exclaimed Don Juan, who had not before interrupted the brother of Cornelia; “no more. From this moment I accept the office you propose to me, and will be your defender and counsellor. I take upon myself the satisfaction of your honour, or due vengeance for the affront you have received, not only because I am a Spaniard, but because I am a gentleman, and you another, so noble, as you have said, as I know you to be, and as, indeed, all the world reputes you. When shall we set out? It would be better that we did so immediately, for a man does ever well to strike while the iron is hot. The warmth of anger increases courage, and a recent affront more effectually awakens vengeance.”

Hearing this, Don Lorenzo rose and embraced Don Juan, saying to him, “A person so generous as yourself, Signor Don Juan, needs no other incentive than that of the honour to be gained in such a cause: this honour you have assured to yourself to-day, if we come out happily from our adventure; but I offer you in addition all I can do, or am worth. Our departure I would have to be to-morrow, since I can provide all things needful to-day.”

“This appears to me well decided,” replied Don Juan, “but I must beg you, Signor Don Lorenzo, to permit me to make all known to a gentleman who is my friend, and of whose honour and silence I can assure you even more certainly than of my own, if that were possible.”

“Since you, Signor Don Juan,” replied Lorenzo, “have taken charge, as you say, of my honour, dispose of this matter as you please; and make it known to whom and in what manner it shall seem best to you; how much more, then, to a companion of your own, for what can he be but everything that is best.”

This said, the gentlemen embraced each other and took leave, after having agreed that on the following morning Lorenzo should send to summon Don Juan at an hour fixed on when they should mount their horses and pursue their journey in the disguise that Don Lorenzo had selected.

Don Juan then returned, and gave an account of all that had passed to Don Antonio and Cornelia, not omitting the engagement into which he had entered for the morrow.

“Good heavens, Signor!” exclaimed Cornelia; “what courtesy! what confidence! to think of your committing yourself without hesitation to an undertaking so replete with difficulties! How can you know whether Lorenzo will take you to Ferrara, or to what place indeed he may conduct you? But go with him whither you may, be certain that the very soul of honour and good faith will stand beside you. For myself, unhappy creature that I am, I shall be terrified at the very atoms that dance in the sunbeams, and tremble at every shadow; but how can it be otherwise, since on the answer of Duke Alfonso depends my life or death. How do I know that he will reply with sufficient courtesy to prevent the anger of my brother from passing the limits of discretion? and if Lorenzo should draw the sword, think ye he will have a despicable enemy to encounter? Must not I remain through all the days of your absence in a state of mortal suspense and terror, awaiting the favourable or grievous intelligence that you shall bring me! Do I love either my brother or the duke so little as not to tremble for both, and not feel the injury of either to my soul?”

“Your fears affect your judgment, Signora Cornelia,” replied Don Juan; “and they go too far. Amidst so many terrors, you should give some place to hope, and trust in God. Put some faith also in my care, and in the earnest desire I feel to see your affairs attain to a happy conclusion. Your brother cannot avoid making this journey to Ferrara, nor can I excuse myself from accompanying him thither. For the present we do not know the intentions of the duke, nor even whether he be or be not acquainted with your elopement. All this we must learn from his own mouth; and there is no one who can better make the inquiry than myself. Be certain, Signora, that the welfare and satisfaction of both your brother and the Signor Duke are to me as the apples of my eyes, and that I will care for the safety of the one as of the other.”

“Ah Signor Don Juan,” replied Cornelia, “if Heaven grant you as much power to remedy, as grace to console misfortune, I must consider myself exceedingly fortunate in the midst of my sorrows; and now would I fain see you gone and returned; for the whole time of your absence I must pass suspended between hope and fear.”

The determination of Don Juan was approved by Don Antonio, who commended him for the justification which he had thereby given to the confidence of Lorenzo Bentivoglio. He furthermore told his friend that he would gladly accompany him, to be ready for whatever might happen, but Don Juan replied–“Not so; first, because you must remain for the better security of the lady Cornelia, whom it will not be well to leave alone; and secondly, because I would not have Signor Lorenzo suppose that I desire to avail myself of the arm of another.” “But my arm is your own,” returned Don Antonio, “wherefore, if I must even disguise myself, and can but follow you at a distance, I will go with you; and as to Signora Cornelia, I know well that she will prefer to have me accompany you, seeing that she will not here want people who can serve and guard her.” “Indeed,” said Cornelia, “it will be a great consolation to me to know that you are together, Signors, or at least so near as to be able to assist each other in case of necessity; and since the undertaking you are going on appears to be dangerous, do me the favour, gentlemen, to take these Relics with you.” Saying this, Cornelia drew from her bosom a diamond cross, of great value, with an Agnus of gold equally rich and costly. The two gentlemen looked at the magnificent jewels, which they esteemed to be of still greater value than the decoration of the hat; but they returned them to the lady, each saying that he carried Relics of his own, which, though less richly decorated, were at least equally efficacious. Cornelia regretted much that they would not accept those she offered, but she was compelled to submit.

The housekeeper was now informed of the departure of her masters, though not of their destination, or of the purpose for which they went. She promised to take the utmost care of the lady, whose name she did not know, and assured her masters that she would be so watchful as to prevent her suffering in any manner from their absence.

Early the following morning Lorenzo was at the door, where he found Don Juan ready. The latter had assumed a travelling dress, with the rich sombrero presented by the duke, and which he had adorned with black and yellow plumes, placing a black covering over the band of brilliants. He went to take leave of Cornelia, who, knowing that her brother was near, fell into an agony of terror, and could not say one word to the two friends who were bidding her adieu. Don Juan went out the first, and accompanied Lorenzo beyond the walls of the city, where they found their servants waiting with the horses in a retired garden. They mounted, rode on before, and the servants guided their masters in the direction of Ferrara by ways but little known. Don Antonio followed on a low pony, and with such a change of apparel as sufficed to disguise him; but fancying that they regarded him with suspicion, especially Lorenzo, he determined to pursue the highway, and rejoin his friend in Ferrara, where he was certain to find him with but little difficulty.

The Spaniards had scarcely got clear of the city before Cornelia had confided her whole history to the housekeeper, informing her that the infant belonged to herself and to the Duke of Ferrara, and making her acquainted with all that has been related, not concealing from her that the journey made by her masters was to Ferrara, or that they went accompanied by her brother, who was going to challenge the Duke Alfonso.

Hearing all this, the housekeeper, as though the devil had sent her to complicate the difficulties and defer the restoration of Cornelia, began to exclaim–“Alas! lady of my soul! all these things have happened to you, and you remain carelessly there with your limbs stretched out, and doing nothing! Either you have no soul at all, or you have one so poor and weak that you do not feel it! And do you really suppose that your brother has gone to Ferrara? Believe nothing of the kind, but rather be sure that he has carried off my masters, and wiled them from the house, that he may return and take your life, for he can now do it as one would drink a cup of water. Consider only under what kind of guard and protection we are left–that of three pages, who have enough to do with their own pranks, and are little likely to put their hands to any thing good. I, for my part, shall certainly not have courage to await what must follow, and the destruction that cannot but come upon this house. The Signor Lorenzo, an Italian, to put his trust in Spaniards, and ask help and favour from them! By the light of my eyes. I will believe none of that!” So saying, she made a fig[2]A gesture of contempt or playfulness, as the case may be, and which consists in a certain twist of the fingers and thumb. at herself. “But if you, my daughter, will take good advice, I will give you such as shall truly enlighten your way.”

Cornelia was thrown into a pitiable state of alarm and confusion by these declarations of file housekeeper, who spoke with so much heat, and gave so many evidences of terror, that all she said appeared to be the very truth. The lady pictured to herself Don Antonio and Don Juan as perhaps already dead; she fancied her brother even then coming in at the door, and felt herself already pierced by the blows of his poniard. She therefore replied, “What advice do you then give me, good friend, that may prevent the catastrophe which threatens us?”

“I will give you counsel so good,” rejoined the housekeeper, “that better could not be. I, Signora, was formerly in the service of a priest, who has his abode in a village not more than two miles from Ferrara. He is a good and holy man, who will do whatever I require from him, since he is under more obligations to me than merely those of a master to a faithful servant. Let us go to him. I will seek some one who shall conduct us thither instantly; and the woman who comes to nurse the infant is a poor creature, who will go with us to the end of the world. And, now make ready, Signora; for supposing you are to be discovered, it would be much better that you should be found under the care of a good priest, old and respected, than in the hands of two young students, bachelors and Spaniards, who, as I can myself bear witness, are but little disposed to lose occasions for amusing themselves. Now that you are unwell, they treat you with respect; but if you get well and remain in their clutches, Heaven alone will be able to help you; for truly, if my cold disdain and repulses had not been my safeguard, they would long since have torn my honour to rags. All is not gold that glitters. Men say one thing, but think another: happily, it is with me that they have to do; and I am not to be deceived, but know well when the shoe pinches my foot. Above all, I am well born, for I belong to the Crivellis of Milan, and I carry the point of honour ten thousand feet above the clouds; by this you may judge, Signora, through what troubles I have had to pass, since, being what I am, I have been brought to serve as the housekeeper of Spaniards, or as, what they call, their gouvernante. Not that I have, in truth, any complaint to make of my masters, who are a couple of half-saints[3]The original is benditos, which sometimes means simpleton, but is here equivalent to the Italian beato, and must be rendered as in the text.when they are not put into a rage. And, in this respect, they would seem to be Biscayans, as, indeed, they say they are. But, after all, they may be Galicians, which is another nation, and much less exact than the Biscayans; neither are they so much to be depended on as the people of the Bay.”

By all this verbiage, and more beside, the bewildered lady was induced to follow the advice of the old woman, insomuch that, in less than four hours after the departure of the friends, their housekeeper making all arrangements, and Cornelia consenting, the latter was seated in a carriage with the nurse of the babe, and without being heard by the pages they set off on their way to the curate’s village. All this was done not only by the advice of the housekeeper, but also with her money; for her masters had just before paid her a year’s wages, and therefore it was not needful that she should take a jewel which Cornelia had offered her for the purposes of their journey.

Having heard Don Juan say that her brother and himself would not follow the highway to Ferrara, but proceed thither by retired paths, Cornelia thought it best to take the high road. She bade the driver, go slowly, that they might not overtake the gentlemen in any case; and the master of the carriage was well content to do as they liked, since they had paid him as he liked.

We will leave them on their way, which they take with as much boldness as good direction, and let us see what happened to Don Juan de Gamboa and Signor Lorenzo Bentivoglio. On their way they heard that the duke had not gone to Ferrara, but was still at Bologna, wherefore, abandoning the round they were making, they regained the high road, considering that it was by this the duke would travel on his return to Ferrara. Nor had they long entered thereon before they perceived a troop of men on horseback coming as it seemed from Bologna.

Don Juan then begged Lorenzo to withdraw to a little distance, since, if the duke should chance to be of the company approaching, it would be desirable that he should speak to him before he could enter Ferrara, which was but a short distance from them. Lorenzo complied, and as soon as he had withdrawn, Don Juan removed the covering by which he had concealed the rich ornament of his hat; but this was not done without some little indiscretion, as he was himself the first to admit some time after.

Meanwhile the travellers approached; among them came a woman on a pied-horse, dressed in a travelling habit, and her face covered with a silk mask, either to conceal her features, or to shelter them from the effects of the sun and air.

Don Juan pulled up his horse in the middle of the road, and remained with his face uncovered, awaiting the arrival of the cavalcade. As they approached him, the height, good looks, and spirited attitude of the Spaniard, the beauty of his horse, his peculiar dress, and, above all, the lustre of the diamonds on his hat, attracted the eyes of the whole party but especially those of the Duke of Ferrara, the principal personage of the group, who no sooner beheld the band of brilliants than he understood the cavalier before him to be Don Juan de Gamboa, his deliverer in the combat frequently alluded to. So well convinced did he feel of this, that, without further question, he rode up to Don Juan, saying, “I shall certainly not deceive myself, Signor Cavalier, if I call you Don Juan de Gamboa, for your spirited looks, and the decoration you wear on your hat, alike assure me of the fact.”

“It is true that I am the person you say,” replied Don Juan. “I have never yet desired to conceal my name; but tell me, Signor, who you are yourself, that I may not be surprised into any discourtesy.”

“Discourtesy from you, Signor, would be impossible,” rejoined the duke. “I feel sure that you could not be discourteous in any case; but I hasten to tell you, nevertheless, that I am the Duke of Ferrara, and a man who will be bound to do you service all the days of his life, since it is but a few nights since you gave him that life which must else have been lost.”

Alfonzo had not finished speaking, when Don Juan, springing lightly from his horse, hastened to kiss the feet of the duke; but, with all his agility, the latter was already out of the saddle, and alighted in the arms of the Spaniard.

Seeing this, Signor Lorenzo, who could but observe these ceremonies from a distance, believed that what he beheld was the effect of anger rather than courtesy; he therefore put his horse to its speed, but pulled up midway on perceiving that the duke and Don Juan were of a verity clasped in each other’s arms. It then chanced that Alfonso, looking over the shoulders of Don Juan, perceived Lorenzo, whom he instantly recognised; and somewhat disconcerted at his appearance, while still holding Don Juan embraced, he inquired if Lorenzo Bentivoglio, whom he there beheld, had come with him or not. Don Juan replied, “Let us move somewhat apart from this place, and I will relate to your excellency some very singular circumstances.”

The duke having done as he was requested, Don Juan said to him, “My Lord Duke, I must tell you that Lorenzo Bentivoglio, whom you there see, has a cause of complaint against you, and not a light one; he avers that some nights since you took his sister, the Lady Cornelia, from the house of a lady, her cousin, and that you have deceived her, and dishonoured his house; he desires therefore to know what satisfaction you propose to make for this, that he may then see what it behoves him to do. He has begged me to be his aid and mediator in the matter, and I have consented with a good will, since, from certain indications which he gave me, I perceived that the person of whom of complained, and yourself, to whose liberal courtesy I owe this rich ornament, were one and the same. Thus, seeing that none could more effectually mediate between you than myself, I offered to undertake that office willingly, as I have said; and now I would have you tell me, Signor, if you know aught of this matter, and whether what Lorenzo has told me be true.”

“Alas, my friend, it is so true,” replied the duke, “that I durst not deny it, even if I would. Yet I have not deceived or carried off Cornelia, although I know that she has disappeared from the house of which you speak. I have not deceived her, because I have taken her for my wife; and I have not carried her off, since I do not know what has become of her. If I have not publicly celebrated my nuptials with her, it is because I waited until my mother, who is now at the last extremity, should have passed to another life, she desiring greatly that I should espouse the Signora Livia, daughter of the Duke of Mantua. There are, besides, other reasons, even more important than this, but which it is not convenient that I should now make known.

“What has in fact happened is this:–on the night when you came to my assistance, I was to have taken Cornelia to Ferrara, she being then in the last month of her pregnancy, and about to present me with that pledge of our love with which it has pleased God to bless us; but whether she was alarmed by our combat or by my delay, I know not; all I can tell you is, that when I arrived at the house, I met the confidante of our affection just coming out. From her I learned that her mistress had that moment left the house, after having given birth to a son, the most beautiful that ever had been seen, and whom she had given to one Fabio, my servant. The woman is she whom you see here. Fabio is also in this company; but of Cornelia and her child I can learn nothing. These two days I have passed at Bologna, in ceaseless endeavours to discover her, or to obtain some clue to her retreat, but I have not been able to learn anything.”

“In that case,” interrupted Don Juan, “if Cornelia and her child were now to appear, you would not refuse to admit that the first is your wife, and the second your son?”

“Certainly not,” replied the duke; “for if I value myself on being a gentleman, still more highly do I prize the title of Christian. Cornelia, besides, is one who well deserves to be mistress of a kingdom. Let her but come, and whether my mother live or die, the world shall know that I maintain my faith, and that my word, given in private, shall be publicly redeemed.”

“And what you have now said to me you are willing to repeat to your brother, Signor Lorenzo?” inquired Don Juan.

“My only regret is,” exclaimed the duke, “that he has not long before been acquainted with the truth.”

Hearing this, Don Juan made sign to Lorenzo that he should join them, which he did, alighting from his horse and proceeding towards the place where his friends stood, but far from hoping for the good news that awaited him.

The duke advanced to receive him with open arms, and the first word he uttered was to call him brother. Lorenzo scarcely knew how to reply to a reception so courteous and a salutation so affectionate. He stood amazed, and before he could utter a word, Don Juan said to him, “The duke, Signor Lorenzo, is but too happy to admit his affection for your sister, the Lady Cornelia; and, at the same time, he assures you, that she is his legitimate consort. This, as he now says it to you, he will affirm publicly before all the world, when the moment for doing so has arrived. He confesses, moreover, that he did propose to remove her from the house of her cousin some nights since, intending to take her to Ferrara, there to await the proper time for their public espousals, which he has only delayed for just causes, which he has declared to me. He describes the conflict he had to maintain against yourself; and adds, that when he went to seek Cornelia, he found only her waiting-woman, Sulpicia, who is the woman you see yonder: from her he has learned that her lady had just given birth to a son, whom she entrusted to a servant of the duke, and then left the house in terror, because she feared that you, Signor Lorenzo, had been made aware of her secret marriage: the lady hoped, moreover, to find the duke awaiting her in the street. But it seems that Sulpicia did not give the babe to Fabio, but to some other person instead of him, and the child does not appear, neither is the Lady Cornelia to be found, in spite of the duke’s researches. He admits, that all these things have happened by his fault; but declares, that whenever your sister shall appear, he is ready to receive her as his legitimate wife. Judge, then, Signor Lorenzo, if there be any more to say or to desire beyond the discovery of those two dear but unfortunate ones–the lady and her infant.”

To this Lorenzo replied by throwing himself at the feet of the duke, who raised him instantly. “From your greatness and Christian uprightness, most noble lord and dear brother,” said Lorenzo, “my sister and I had certainly nothing less than this high honour to expect.” Saying this, tears came to his eyes, and the duke felt his own becoming moist, for both were equally affected,–the one with the fear of having lost his wife, the other by the generous candour of his brother-in-law; but at once perceiving the weakness of thus displaying their feelings, they both restrained themselves, and drove back those witnesses to their source; while the eyes of Don Juan, shining with gladness, seemed almost to demand from them the albricias[4]Albricias: “Largess!” “Give reward for good tidings.”of good news, seeing that he believed himself to have both Cornelia and her son in his own house.