by Gustavo Bueno (España no es un mito. Madrid: Temas de Hoy, 2005. Pages 241-290)

Translated by Brendan Burke

© 2010 FGB · Oviedo

1

Against the interpretation of Don Quixote as a symbol of universal solidarity, tolerance, and peace

2005. All of Spain celebrates the fourth centennial of the publication of Don Quixote (the printing itself had already been completed by December 1604). This celebration clearly supports the thesis I have maintained throughout this book – that all regions and “cultures” of Spain together share a common Spanish culture.{1}Hundreds of conferences spring up in every city and capital of each autonomous region, be they “historical” or regions “without history”: we see contests, new editions, public readings (both collective and individual), expositions, workshops, and interpretations of all kinds – psychiatric interpretations (Cervantes may have admirably described “Capgras syndrome”), ethical interpretations (Don Quixote is fortitude and generosity), and moral interpretations (Don Quixote symbolizes, in modern times, the virtues of the knight estate in the feudal period). And the readings go on – Don Quixote becomes the symbol of strictly literary values (the modern novel), or of values with political implications (European values, perhaps?), or even further, of universal values that convert him into a symbol of Man itself, of human rights, of tolerance, or of peace: “Don Quixote is part of the World’s Heritage.”

These political interpretations of Don Quixote as a tolerant pacifist have become particularly popular among socialist leaders from that “village” of Alonso Quijano, the “Knight of La Mancha” as he is more commonly known. This village has now been transformed into an autonomous region, Castilla-La Mancha – one with the legal capacity to enact a law which, considering that “Don Quixote is a symbol of humanity and a cultural myth that La Mancha feels honored to call its own”, seeks to create a “network of solidarity which, basing itself in the value of a common language, will work to achieve the equality and development of all its towns, fundamentally through education and culture” in order “to contribute to the social, cultural, and economic development of Castilla-La Mancha…with the goal of promoting and spreading the universal values of justice, liberty, and solidarity which Quixote symbolizes.”{2}

José Bono, the president of Castilla-La Mancha during the enactment of this law, was named Minister of Defense after the Madrid bombings of March 11, 2004: a position which, within democracies of pacifist ideology, replaces the previous position of Minister of War, even though both the current democratic Minister of Defense and the past non-democratic Minister of War dealt with the same things: cannons, missiles, battleships, helicopters, and more generally, in an industrial society, with firearms (by no means with lances, nor swords, nor Mambrino’s helmet). Bono’s pacifism, so unlike Quixote’s, has led him so far as to ask that the word “war” be removed from the 1978 Spanish constitution. He has yet to ask for the dissolution of the Army (perhaps in order to justify the intervention of the Spanish Army in Afghanistan), although it does seem that by removing the troops from Iraq, the Socialist government would like to transform the Corps into a sort of Firefighters without Borders, ready to deploy off to Afghanistan to keep an eye on any fires that might break out by chance during the electoral period in this new, projected democracy.

In any case I don’t think it’s necessary to get into the debate about the political reach that these projects of justice, perpetual peace, dialogue, tolerance, and solidarity might have – projects propagated by fundamentalist, democratic governments that commemorate Don Quixote and represent him in their own image and likeness. I do, however, see it necessary to conclude that if they want to keep maintaining their pacifism and universal solidarity, then they must back off their devotion to Don Quixote, for in no way can Don Quixote be taken as a symbol of solidarity, peace, and tolerance. Let them continue their pacifist and anti-military politics, but no longer by taking the name of Don Quixote in vain.

If Don Quixote is the symbol of something, he is neither the symbol of “universal solidarity” nor of “tolerance”. For what solidarity did Don Quixote show towards the guards watching over the chain-gang of galley slaves? His solidarity with the convicts implies a lack of solidarity with the guards, and cannot therefore be called universal. If Don Quixote is the symbol of something, he is the symbol of weapons, of intolerance – an intolerance so great that he cannot stand it when Master Pedro puts on a puppet show of the story Melisendra, who is about to be captured by a Moor king. This is unacceptable for Don Quixote and so he draws his sword, leaps in front of the stage, and demolishes the puppeteer’s entire show. And who can conceive of an unarmed Don Quixote? It’s true that in the final chapter he hangs up his armor, just as a monk hangs up his habits; however, for the priest or monk this implies the rebirth toward a new life, one in which his mistress is elevated to the status of wife, while for Don Quixote hanging up his armor signifies the step which will immediately lead him to his death.

2

Don Quixote is not a tautegorical symbol

Don Quixote is a symbol, or at least can be interpreted as one if we admit Schelling’s disputed distinction between tautegorical and allegorical symbols.{3}

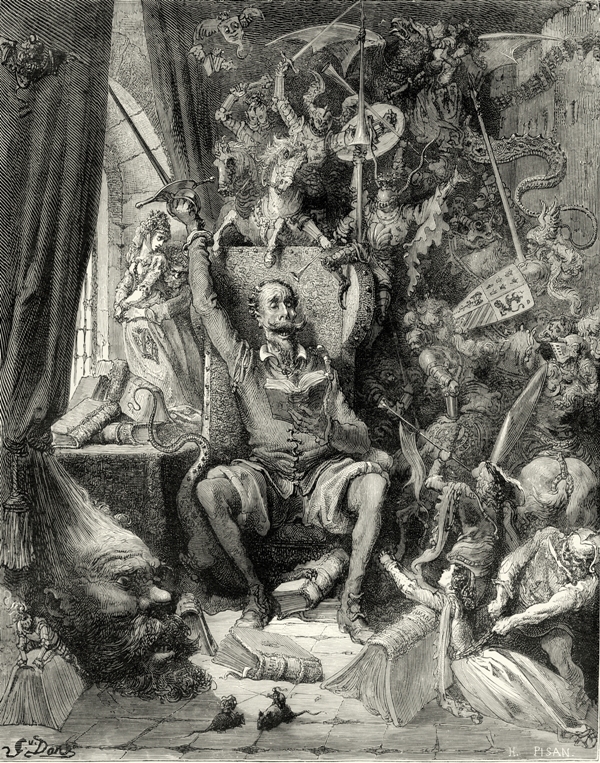

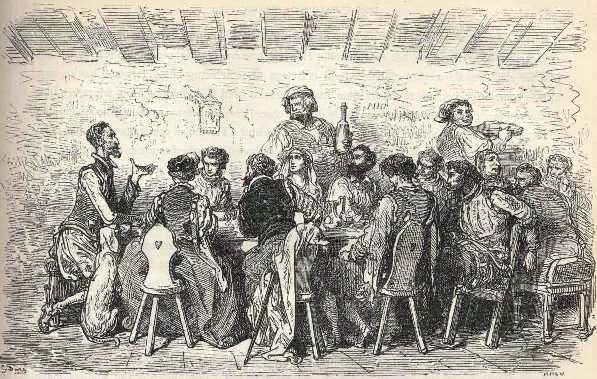

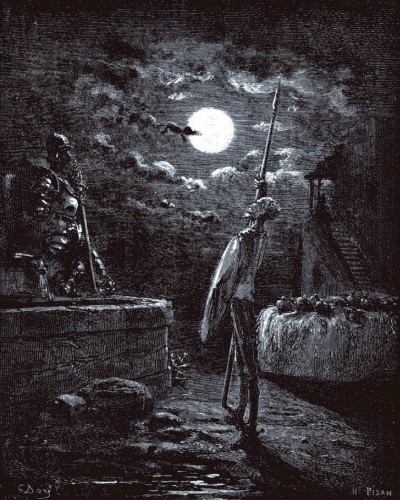

Don Quixote has been represented (and still continues to be represented, without calling it “representation”) as a tautegorical symbol – one that expresses the same thing as itself. Those who see El Quixote as a strictly literary work, immanent – without references beyond its own imaginary figures – interpret it as a tautegorical symbol, or as a collection of tautegorical symbols. These imaginary figures would exhaust themselves as they inhabit a social imaginary. This social imaginary, however, isn’t made up by representations or “mental images” (images that compose those “mentalities” studied by “Marxist historians” who some years ago embraced the so-called History of Mentalities), but instead by real physical images – ones painted, for instance, in the 17th and 18th centuries by Antonio Carnicero, José del Castillo, Bernardo Barranco, José Brunete, Gerónimo Gil, or Gregorio Ferro. (Not to mention those painted in the 19th by José Moreno Carbonero, Ramón Puiggarí, Gustave Doré, Ricardo Balaca or Luis Pellicer, or even in the 20th by Daniel Urrabieta Vierge, Joaquín Vaquero, Dalí, or Saura…and not counting the innumerable drawings of Quixote for both adults and children in comics, movies, and theatrical representations).

Moderately widening the field of “tautegorical literary immanence”, we could also include the usual interpretation of Quixote as a literary work itself addressing other literary works – books of chivalry. This address, of course, would be directed toward those chivalrous errant knights in print, not those in real life, like Hernán Cortés or Don Juan de Austria, under whose flags Cervantes himself fought.

These tautegorical interpretations could even be supported by the speech that the innkeeper delivers against the priest, who attacks those books as being full of lies, absurdities, and nonsense, and for destroying interest in real historical figures, such as Gozalo Hernández de Córdoba or Diego García de Paredes: “A fig for the Great Captain and another for that Diego García character,” exclaims the innkeeper, through whom some believe Cervantes himself to be speaking.{4}

I don’t deny that these literary interpretations of the immanence of Quixote make sense; what I do question is the legitimacy of considering tautegorical symbols as symbols – at the very most, these tautegorical symbols constitute a limited case of the idea of the symbol, a limit in which the symbol ceases to be a symbol, just as a causa sui ceases to be a cause. For a symbol, as an alotetic figure, precisely expresses references distinct from the actual body of the symbol.{5} It does so because the references of the symbol must also be corporeal: each part of the fragmented ring handed to the main participants of the ceremony is a symbol of the other part; the Nicene Creed is a “Symbol of Faith” because each group of faithful that recites their verses refers to those that recite successive ones, and so the community of faithful forms a living community, one which is a real part of the active church.

Accordingly, Don Quixote is not a tautegorical symbol in the most literal sense, the sense in which Magistral de Pas understood the verse “and the Word became flesh.” “Did Don Fermín believe in this verse?”{6}Strictly speaking (and according to Clarín), Don Fermín believed in the red letters written on a panel on an altar that read, “et verbum caro factum est.” Figures, interpreted as strict, allegorical symbols, refer us beyond the literature and to real figures in civil, political, or social history.

3

Don Quixote: a clinical history?

Some critics suggest that Cervantes, through the figure of Alonso Quijano, meant to represent some actual individual, one he might have met directly or through some friend or writer. Accordingly, the real reference of Don Quixote would be Alonso Quijano – an individual made of flesh and blood, but affected by a specific type of insanity that Cervantes intuitively managed to discover and identify without being a doctor or a psychiatrist. In 1943, Menéndez Pidal discovered the figure of Bartolo in the comic sketch Entremeses de los Romances; Bartolo was a poor laborer who went mad for having read too many romances. Cervantes may have been inspired by him, or perhaps by Don Rodrigo Pacheco, a marquis from Argamasilla de Alba, who also went mad reading books of chivalry.

Psychiatrists have, naturally, tended to interpret Don Quixote from categories typical of their trade. In the 19th century, Dr. Esquirol interpreted Don Quixote as a model of monomania (a term of his own invention). More recently, Dr. Francisco Alonso-Fernández has published an interpretation of Don Quixote in which the novel is considered as a sort of clinical history of a patient suffering from a disorder that Cervantes managed to establish. In this interpretation, Cervantes very closely approximates what is today known as delusional autometamorphosis, a syndrome related to other delusional syndromes such as Capgras or Fregoli. In consequence, Alonso-Fernández proposes that Alonso Quijano – not Don Quixote – should be considered the authentic protagonist of the novel. As he argues, it was in effect Alonso Quijano who suffered from the delusional disorder that identified him with Don Quixote, who only existed in his mind; again, it was Alonso Quijano who managed to recover from the disorder, thanks to the care of the graduate Carrasco, the priest, the barber, and “a fever that kept him in bed for six days.”{7} Alonso-Fernández stresses that this incident did not pass unnoticed to “the perceptive clinical eye of the eminent doctor Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra.”{8}

I must thank my dear friend Dr. Alonso for his demonstration that Alonso Quijano suffered from a disorder that Cervantes was able to describe with impressive precision. Such a demonstration, of course, can only be explained if we admit that Cervantes had known and differentiated other specific cases – as he may have done with the insanity of the lawyer of glass in his short story of the same name, El Licenciado Vidriera. In any case, however, neither Don Quixote nor the lawyer Vidriera are purely “literary creations”.

Are we so then to accept that Cervantes proposed the “clinical description” of a specific type of disorder as his literary objective?

Not necessarily, as it could be the case that Cervantes was using his description of a specific type of disorder as the symbol of another reference: the reality of certain people in Spain (not Spain itself, as many argue), a reality in which men, according to many accounts, had gone mad either because they went to America (as some say) or because they stopped going (as I, and others, say). The former argue that they went mad because they went to America in search of El Dorado or because, recalling a book of chivalry (Las Sergas de Esplandián), they named California after an imaginary kingdom of Amazons, or Patagonia after the tribes of monstrous savages in another book, El Primaleón. Even further, it would be possible to extend the symbolism of Don Quixote’s madness to places found in Spain, and not in America, Italy, or Flanders – to anywhere in La Mancha, or to anywhere in Spain or Portugal where Christian parishioners, while present in churches witnessing the transformation of the Eucharist bread and wine actually saw the flesh and blood of Jesus Christ. Don Quixote, slashing the wine skins in the inn, believes he sees spilled blood where there is only wine: is Cervantes here trying to describe a type of disorder similar to that of someone who, upon hearing the consecration, prepares to drink wine that has been turned into blood?

It’s one thing that Don Quixote displays certain disorders that, far from being merely literary, have a clinical consistency (which would obviously oblige us to consider Don Quixote as an alotetic figure, not a tautegorical one); it’s another thing altogether to claim that Cervantes not only proposed to make (finis operantis) but indeed had made (finis operis) as his literary goal the early description of a delusional disorder suffered by a certain Alonso Quijano. For is not Alonso Quijano himself a literary figure? Even further, does not Cervantes also use the disorder systematized in Don Quixote as a symbol of other actual figures who themselves weren’t considered victims of Capgras or Fregoli delusions? Perhaps the fever in Don Quixote’s final days (even while admitting the diagnosis of Cervantes’s clinical eye) could also symbolize Spain’s fever during years of profound crisis?

Interpreted as allegorical symbols, Don Quixote’s disorders would then refer, not to actual lunatics that a psychiatrist might see in a hospital or clinic, but to real historical figures who might pass as extraordinary or even heroic. Another matter is to identify these figures and determine the possible reach that the use of delusional symbols as symbols of themselves might have.

4

The individual and the pair of individuals

A human figure, such as Don Quixote, never exists in isolation: one person always implies others who relate to one another in either peaceful or hostile coexistence. In other words, an individual in and of itself is an absurdity, a metaphysical entity, and as such the attempt to interpret Don Quixote as a symbol of some isolated individual, whether sane or mad, is mere metaphysics – an individual in itself cannot exist because existence is co-existence.

Not even a king or emperor may be considered an individual, in the sense of an isolated being. Therefore, Aristotle’s famous classification of political societies into three usual groups – monarchies, aristocracies, and republics – is a classification better suited to political-science fiction, even though it continues to be our reference to this day. According to Aristotelian criteria either one commands, or some command, or all (the majority) command. But these criteria don’t help us distinguish monarchies from aristocracies, for the simple reason that “one” cannot command because “one” does not exist: even the most absolute monarch does not command alone, but as the head of a group.

Two is the numerical minimum of people to coexist; perhaps for that the interpretations of human relations from a dualist viewpoint (one based on pairs of individuals) reach nearly universal consensus (especially pairs made up by opposite individuals – either in their grammatical gender or according to other criteria of opposition: tall/short, clever/dumb, old/young, fat/thin, etc.).{9} In this viewpoint, people are never alone but are rather paired up with others who oppose them by their different and contradictory attributes. And so if the elements of a pair are considered “equal”, then the opposition between them must emerge from their own coexistence, which is the case, for example, with enantiomorphic objects in which opposing (equal but incongruent) figures appear, such as the incongruity of our two hands – they are equal, but opposing (left and right). Adam and Eve are the prototype of the first pair – opposite in gender, but accompanied by a variety of other opposing pairs; the Dioscuri (Castor and Pollux) were seen in the Battle of Lake Regillus mounting their white horses and fighting between themselves.{10}

Don Quixote, from this dualist viewpoint of coexistence, has always been considered in relation to Sancho. The pair “Don Quixote and Sancho” and the most peculiar set of oppositions established between them (lord/servant, knight/squire, tall/short, thin/fat, idealist/realist…) have often been considered as the originals for later reproductions in other famous literary pairs, from Sherlock Holmes and Watson to Asterix and Obelix (who break down some of the oppositions of attributes, oppositions considered characteristic: the leptosomatic opposition of tall and thin, and the pyknic one of short and fat).

There are, however, very serious reasons to conclude that these dualist viewpoints are only a fragment of a more complicated structure. Adam and Eve, for example, are only a fragment of a society they make up together with their sons Cain, Abel, and Seth. Don Quixote and Sancho are usually thought of in terms of abstract oppositions like idealism and realism or utopic and pragmatic. But these oppositions fall apart immediately: they suppose that idealism is some sort of personal disposition geared to transcend the immediate horizon of the facts of life, and thereby impulses people toward altruism or glory. Sancho, then, does not oppose Don Quixote because he too (from the beginning, not only in the second part, as some critics contend) is quixoticized. Getting himself into all sorts of dangers,he accompanies Don Quixote not only to acquire riches (which itself would be enough, given that someone who wants to acquire riches by putting his life in danger is no longer a pragmatic realist in the traditional sense) but also to help his wife Teresa Cascajo ascend the social ladder. Sancho is not the sort of villain Spaniard that so many villainous historians imagine him to be in their assumption that his and others only motivation for signing up for the infantry or navy was the satisfaction of their hunger (I have in mind Alfredo Landa’s film La Marrana).

It is of great importance here to warn of the incompatibility between these dualist structures and the principles of philosophical materialism, insofar as the latter implies the Platonic principle of symploke.{11} In his Sophist, Plato established the two premises which must be presupposed in every rational process: the first is a principle of connection between some things and others – “if everything were disconnected from everything else, rational discourse would be impossible” – and the second is a principle of disconnection between some things and others – “if everything were connected to everything else, rational discourse would be impossible.” Therefore, if we want to rationally approach reality, we must suppose that neither everything is causally connected to everything else, nor is everything disconnected from everything else; that is, we must suppose that things are interwoven (in symploke) with other things, but not with everything.

But when we apply the dualist structure to a given social group (the circle of individual human beings, for example), we find that reality is presented to us as a plurality of pairs disconnected from each other (since we suppose that the terms of each pair refer integrally to one another). In effect, the connection of the terms of each pair is completed internally, whether each individual is considered to be correlated or conjugated with the other. Each “isolated pair” introduces a reciprocal dependency between its terms, one that permits the pair to be treated as a “monist” unity, a dipole, whether their relationship be harmonious or discordant. As such, global reality is seen as a multiplicity composed of infinite pairs whose interactions are merely random. In the case where the dualist viewpoint is applied to a unique pair – coextensive with “reality itself” (in Manichaeism with Ormus and Ahriman, in Gnosticism with the dyad Abyzou/Aletheia, or in Taoism with the Yin and the Yang) – this “cosmic dualism” practically becomes a monism, even without having to consider the possibility that one of the dualist terms would end up defeating or absorbing the other. It would be sufficient for them to remain eternally different, even while complementing or separating each other, until death (“one of those two Spains will freeze your heart”).{12}

5

Triads

The most basic structure compatible with the principle of symploke of philosophical materialism is the ternary structure. In a triad (A, B, C), each member is involved with the others, but at the same time it is possible to recognize binary coalitions ([A, B], [A, C], [B, C]) in which the third member, while segregated, still remains associated with the others. The organization of any field constituted by individuals also contains the possibility for each triad to be involved with other triads through some common unity, thus giving rise to enneads (3 x 3), dozens (3 x 4), and so on. In these pluralities organized in triads, enneads, and dozens, the principle of symploke is adequately satisfied. Both the connection (not total) of some things with others, and the disconnection (or discontinuity) of some things with others (which will follow their own course), can be affirmed from this plurality.

This conception of reality (or of its regions) as organized in triplets is just as old as conceptions organized dualistically. Dumézil argued years ago that it was present in the famous trinities of the Indo-European gods: Zeus, Heracles, and Pluto, or Jupiter, Mars, and Quirinus, or the Capitoline Triad of Jupiter, Minerva, and Juno, or its Germanic transformation in Odin, Thor, and Freyja.

In Christianity, and more specifically in the Catholic tradition (to which Don Quixote undoubtedly belongs), the fundamental triad is represented in the dogma of the Trinity: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit which proceeds from the Father and the Son together (in this final aspect Roman Catholics differ from Greek Orthodox, for whom the Holy Spirit is some sort of emanation from the Father, without the participation of the Son).

This Catholic trinity, however, needn’t necessarily be interpreted as just a particular case of other Indo-European trinities. In Roman Christianity the dogma of the Trinity developed gradually, and the appeal to the Holy Spirit was probably related to the constitution of the Universal church itself, one which had no parallel in its social structure with the known social structures of the Greeks (such as the family or the state). Albeit heretically, Sabellius held that the Holy Spirit represented the Church as a feminine entity (“the Holy Mother Church”). In addition, in some Germanic trinities one of the members is feminine – Odin, Thor, and Freyja. This may be due, however, due to contamination from Christianity, with the Germanic liturgy reflecting a Christian one: “In the name of Odin, Thor, and Freyja.” In either case, it’s obvious that both the trinity of Gaeta and Our Lady of the Rock of France, to whom Sancho entrusts Don Quixote as they descend from the Cave of Montesinos (II,22), are manifestations of the genuine Trinity of Catholicism (the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit).

6

The Triads of Don Quixote

Let us leave aside the dualist organization that imposes upon us the association in pairs between Don Quixote and Sancho, even if such an association may be very fundamental (in which the two are sometimes explained by their complementarity and at other times for their conjugation: Don Quixote maintains the unity between the different episodes of his quest through Sancho, who maintains the unity between the episodes of his quest through Don Quixote). Leaving that organization aside, the tripartite restructuring becomes patently obvious, even if Cervantes wasn’t aware of it. (The case would be even more interesting if this were an objective structure that imposed itself independently of the author’s will).

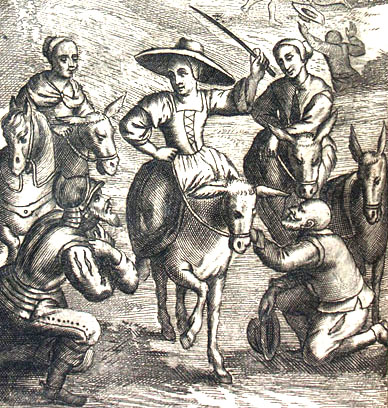

What is sure is that Don Quixote always appears as a member of the trinity that he makes up with Sancho and Dulcinea. Of course this doesn’t mean that the members of this trinity are not involved at the same time with other different trinities: Don Quixote, for instance, always forms a triangle with his housekeeper and his niece (II, 6); Sancho always appears involved with his wife, Teresa Cascajo, and his daughter, or with the priest and the barber (I, 26); Dulcinea, in her most real role as a peasant girl, comes towards Sancho on a jackass, along with two other peasant girls: “And events fell out so well for [Sancho] that when he got up to climb on his dun he saw three peasant girls coming towards him from El Toboso on three jackasses, or she-asses, because the author isn’t explicit on this point.” And a little later, when Sancho tells Don Quixote that he has seen Dulcinea: “They emerged from the wood and saw the three peasant girls not far away. Don Quixote surveyed the road to El Toboso, and since all he could see was these three peasants he became alarmed and asked Sancho if the ladies had been outside the city when he’d left them.”{13}

In any case, the basic trinity around which Don Quixote seems to move throughout the book is the one he makes up with Sancho and Dulcinea. Facing the Catholic Trinity (as my hypothesis obliges), it must be conceded that Don Quixote corresponds to the role of Father, Sancho to that of Son (just as his sire Don Quixote calls him time and time again), and regarding Dulcinea, she must be put in correspondence with the Holy Spirit, which Sabellius interpreted as a feminine entity, as the Mother Church. As an ideal figure, how can it be ignored that she comes from both the Father (Don Quixote) and the Son (Sancho)?

Don Quixote, of course, conceives the figure of Dulcinea. Although her real name was Aldonza Lorenzo, the young peasant daughter of Lorenzo Corchuelo and Aldonza Nogales, quite good-looking (I, 25) and of whom Don Quixote was in love for a time, she was nonetheless born as Dulcinea by Don Quixote’s “decree”, when it seemed right to him to give her the title of “Mistress of His Thoughts.” But Sancho too contributed to the birth and reinforcement of the figure of Dulcinea, an upright and polite girl, “not at all priggish” and “a real courtly lass”: “And now I can say, Sir Knight of the Sorry Face, that not only is it very right and proper for you to get up to your mad tricks for her sake – you’ve got every reason to give way to despair and hang yourself, too, and nobody who knows about it will say you weren’t justified, even if it does send you to the devil.”{14}

This figure thus conceived would have remained as the shadow of a merely imagined memory if it had not been for Sancho’s diligence to find la señora Dulcinea, that is, to establish the link between the figure of the memory and some real counterpart, a link that must be reestablished, if not with the brave Aldonza, then with the moon-faced, flat-nosed peasant (II, 10). And so it turns out to be Sancho, not Don Quixote’s infirm and delirious mind, who bows and pretends to salute Dulcinea, who takes the figure of the moon-faced, flat-nosed peasant. Don Quixote, on his knees next to Sancho, also looks with “clouded vision and bulging eyes” at a peasant who Sancho called queen and duchess. The peasant, who had made the figure of Dulcinea, prods her poultry with a nail that she was carrying and the poultry breaks into a canter across the field, dumping Lady Dulcinea among the daisies. “Don Quixote rushed to pick her up and Sancho hurried to put the pack-saddle…Don Quixote went to lift his enchanted lady in his arms and place her on the ass; but the lady saved him the trouble by jumping to her feet, taking a couple of strides backwards, bounding up to the ass, bringing both hands down on its rump and vaulting, as swift as a falcon, on to the pack-saddle.” Sancho said to Don Quixote, “Our lady and mistress is nimbler than a hobby-hawk, and she could teach the best rider from Cordova or Mexico how to jump on to a horse Arab-style!…And her maids aren’t being outdone, they’re going like the wind, too!”

Is it not obvious here that Cervantes is trying to linger in the description of the poetic vision of the peasant that Sancho offers to Don Quixote by drawing attention to her agility while concealing the moon face and flat nose that Don Quixote also sees? In either case, the transfiguration of the peasant’s figure into Dulcinea cannot be attributed to the endogenetic psychological process of a madman in the midst of a delirious hallucination. Don Quixote does not see Dulcinea, but rather, reinforced by Sancho, sees an agile peasant girl (moon-faced and flat-nosed). In no way, therefore, does he suffer from some hallucination: “Because I would have you know, Sancho, that when I went to replace Dulcinea on her palfrey (as you call it, although I thought it was a donkey), I was half suffocated by a blast of raw garlic that poisoned my very soul.” Cervantes seems to take great care here in stressing that if Don Quixote relates this peasant with Dulcinea it’s because of Sancho. Dulcinea is seen here as a matter of faith, not as a hallucination – faith in the “relevant authority” of Sancho, whose word Don Quixote trusts and believes. Seeing these three villagers (announced as Dulcinea and her duchesses) come out of the wood, Don Quixote says:

“All I can see, Sancho, ” said Don Quixote, “is three peasant girls on three donkeys.”

“God save my soul from damnation!” Sancho replied. “Is it possible for three palfreys or whatever they’re called, as white as the driven snow, to seem to you like donkeys? Good Lord, I’d pull out every single hair on my chin if that was true!”

“Well, I am telling you, friend Sancho, ” said Don Quixote, “that it is as true that they are asses, or maybe she-asses, as it is that I am Don Quixote and you are Sancho Panza; or at least this is how it seems to me.”

Don Quixote’s resistance to see the miracle of the peasant girl’s transfiguration into Dulcinea – a miracle which he must believe for his faith in Sancho’s authority (who on other occasions shows himself so critical of his master’s hallucinations: the windmills, the flock of sheep…) – receives a “theological” explanation: Don Quixote says, “If I don’t see Dulcinea in the figure of this peasant, it’s not because it isn’t her, but because the malicious enchanter is hounding me, and has placed clouds and cataracts over my eyes, and for them alone and not for other eyes has altered and transformed your [Dulcinea’s] face of peerless beauty into that of some poor peasant wretch.” If psychiatrists insist on seeing delirium here, they will have to add that they are not dealing with a hallucinatory delirium (that of seeing a peasant girl as Dulcinea), but instead a delirium of “theological rationalization” meant to explain why this peasant that I see here is not the Dulcinea that Sancho sees there. Psychiatrists might also recognize this same delirium of theological rationalization in Saint Thomas, when he tries to explain why the piece of bread and cup of wine that the priest holds at the altar are in reality the miraculous transmutation of the invisible, intangible body of Christ. And what psychiatrist would dare diagnose Saint Thomas Aquinius as a madman?

Don Quixote’s madness is seen both in his behavior toward Aldonza Lorenzo and the anonymous peasant as well as, most obviously, in his behavior toward the dukes, who themselves are responsible for all the “deliriums” (in reality, the ploys) that Don Quixote and Sancho experience in their company (including the scenes of Clavileño or the island of Barataria). This madness is not only a psychological process that would have affected Alonso Quijano. It is also (and primarily) a social process triggered by the people who surround Don Quixote and who act as Cartesian evil geniuses, deceiving him even while trying to help or even entertain him. These evil geniuses act on Don Quixote, but as counter-figures of those that act through Mephistopheles when he goes to present himself before Faust: “Part of that power which would do evil constantly and constantly does good.”

As such, it’s untenable to attribute madness and delirium to Don Quixote while reserving prudence and common sense for Sancho. If Don Quixote is mad because he takes off on wild adventures, so too is Sancho, who accompanies him not only on the first nor on the second outing, but also on the third: “’Look, Teresa’, Sancho replied. ‘I’m happy because I’ve made up my mind to go back into service with my master Don Quixote, who’s riding off in search of adventures for a third time, and I’m going with him again, because my needs force me to.’”{15}

7

The stage of El Quixote contains three types of references: circular, radial, and angular

From the general presupposition that a singular person always implies a plurality of people, I have tried to outline the structure of this plurality, the one in which the characters of Don Quixote operate.

Rejecting both monist structures (that attribute to a person the original situation of an absolute, solitary person, in the “sublime solitude” of the neo-Platonic God, “alone with the Alone”) and binary structures (dualist, dioscuric, or Manichean) together as metaphysical, I have found it convenient to operate with interwoven tripartite structures in my interpretation of Don Quixote. Furthermore, these trinitary structures can give rise to other, more complex structures such as enneads or dozens, which are found in the novel in the form of the remembrance of the twelve signs of the Zodiac, the twelve apostles, or the twelve Knights of the Round Table.

The hermeneutic discipline that imposes this structural postulation is quite clear: to systematically avoid treating Don Quixote (or any other character) as if he were (even in his soliloquies) an ab-solute character, or a character attached to his complement, albeit in a Manichean way (the same way that inspired those famous verses of Antonio Machado – his talent offered little more – that the “Spanish Left” took as emblem for decades: “Little Spaniard just now coming into this world, may God keep you. One of those two Spains will freeze your heart”).{16} I would like to systematically induce the investigation into the different connections between the characters of Quixote, without having to leave the novel itself or look beyond its immanence for references outside the text and its scenes (references that nonetheless must be found at the proper time).

As has been said many times, Don Quixote is a novel written from a theatrical point of view (Diaz Plaja observed that Quixote is the only novel whose central character is always dressed up). Herein lies its potential to be made into sculptural or pictorial representations, and later into cinematographic and televised ones. Cervantes offers us characters in well-defined scenes. Various characters are always moving in these scenes, at least in principle (there are, of course, exceptions with a single character speaking in a monologue or two speaking in dialogue); the triangle is the elemental structure of the theater as well.

A theater stage (much like that of Cervantes’s great novel) cannot be restricted to the limits of its own physical space. It is a place in which individual actors, by putting on their masks (per-sonare, pros-opon), begin to act as people and therefore it is a part of a circle of human beings, a part of anthropological space.

Beyond the circular dimensions (the relationships of people with other people) – those in which personae move and in which drama, comedy, and tragedy develop – a cosmic dimension also corresponds to the stage. In this dimension geographical and historical references external to the immanence of the stage are both included in and internally involved with the stage (I call these radial references – this network of relationships and interactions that human beings maintain with the impersonal things which surround them).{17} As I will try to demonstrate in what follows, it would be impossible to try to understand the philosophy of Don Quixote – a philosophy that remains hidden or buried beneath literary and cinematographic images – on the fringes of these references.

Finally, in addition to references and figures contained within both the circle of human persons and the radial region of space, the stage also contains figures and references that extend beyond this circle and region. For although they are personal (a condition very similar to human beings, in that they have appetites, knowledge, and feelings) they are not of human nature (I call these references angular – a region of anthropological space that includes certain numinous animals, demons, angels, devils, etc…).

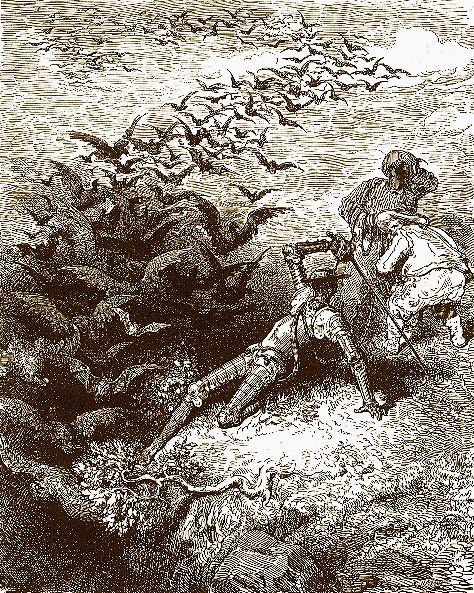

In Quixote there are various angular references to devils, omen-bearing birds (like the countless huge ravens and rooks that flew out from the undergrowth covering the Cave of Montesinos), and some monkey that speaks “in the style of the devil.”{18} Further references are made to giants, like the giant Morgante (affable and polite) who was one of the three to face Roldán in Amadís, or the giant Caraculiambro, lord of the island of Malindrania, who Don Quixote hopes to vanquish in battle in order to send him to present himself to Quixote’s sweet mistress. And, of course, we must count others among these non-human beings: the Trinity of Gaeta already cited, or those of Our Lady of the Rock of France – the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit to whom Sancho entrusts Don Quixote as they descend from the Cave of Montesinos. (Nonetheless, it’s always important to keep in mind that Cervantes insists time and time again that he doesn’t want to get caught up in matters reserved for the Catholic faith.)

Let’s translate all of this into our language: Cervantes affirms that he always wants to remain in the human (circular), cosmic (radial), and religious (angular) stage. (Focusing on the unique rhythm that he seems to attribute to finite and immanent matters, he seems to set aside the indefinite and transcendent rhythm of matters that would concern the Catholic Church.)

8

The stage of Don Quixote does not refer to “anthropological space” in general, but rather to the Spanish Empire

How then are we to determine the references (beyond the novel’s stage) of the human personae, the radialcontents, or the angular entities that all figure in the “immanence” of this stage?

It could be said that such references aren’t defined in Quixote, which is another way to say they don’t exist, or at least that they don’t exist as definite references. Accordingly, the circular references of Don Quixote, Sancho, and Dulcinea would have to refer to “Humanity” in general (figures of humanity that we could find in any place or time), and this is where some place the universality commonly attributed to Cervantes’s work. Likewise, any of the contents of the cosmic, geographical, or historical world could be taken as the novel’s radial references; and, of course, any references that gathered the adequate characters in any time and place would be valid as angular references for the book. In other words, the references of Don Quixotewould be panchronic and pantopic, expressed positively; expressed equally but negatively, they would be uchronic and utopic – therein lies the root of its universality.

Nevertheless, and notwithstanding the possibility of these “universalist” interpretations (the foundation of ethical and psychological interpretations which direct their interpretations toward the characters of Quixoteand their idealism or realism, their fortitude or avarices, and so many other characteristics common to the “human condition”), I prefer to limit myself to the very precise (and far from scarce) historical and geographical interpretations of Don Quixote which I consider sufficient (if not necessary) conditions in order to penetrate its meaning.

In short, it seems to me (and many other critics) that the stage of Don Quixote, as far as it is a symbol, refers to very precise historical and geographical references. Undoubtedly, these references can be put to the side if one remains in humanist, ethical, or psychological interpretations of the novel. However, once we reinterpret the many historical and geographical references that appear throughout Quixote, then political interpretations of it impose themselves – interpretations which, in one way or another, revolve around the meaning of the Spanish Empire, of the fecho del Imperio, to use formula that Alfonso X (“the Wise”) used four centuries earlier.{19}

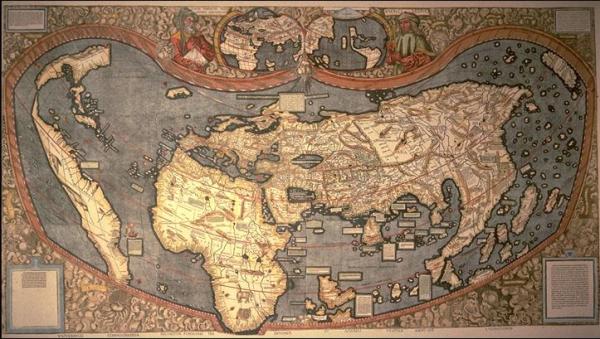

According to these political interpretations, Cervantes offers in his stage an interpretation of the Spanish Empire as the first “generating empire” that reached it peak throughout the 15th and 16th centuries (the English and Dutch Empires would have been raised from the Spanish Empire, initially as its predators).{20}In this interpretation, the Spanish Empire would have reached its highest peaks in 1521 with the conquest of Mexico, and later of Peru and Flanders, and above all in 1571 in Lepanto, where the Ottoman Empire, which was seriously threatening Europe, was halted. Cervantes took part in this battle under the command of Don Juan de Austria and there he lost use of his left arm, which served as a lifelong memory of the reality of the Muslim offensive. In addition to this loss, he was taken prisoner by the Moors and held captive for five years in Algiers until he was set free by a paid ransom.

(A certain minister who fills Zapatero’s government quota, whose name I cannot quite recall, shines with the patent ignorance common to the naive pacifism of her group, declaring in El País on May 19, 2004: “I also think that our projects in the Mediterranean are important. If many of us have refused to take part in the atrocity of this war [Iraq] it’s because an old relationship with the Arab world is still alive…Cervantes, to take just a single example, was in Algiers, in Oran…We have to be aware of our history to know who we are.”)

However, in 1588, the date of the Spanish Armada’s main defeat (although not of its destruction nor or a defeat of the still fearsome power that Spain represented for England, Holland, and France), an inflection takes place in the course of history. Spain hasn’t entered into a decrepit situation, as it will still remain a great world power for two more centuries (the 17th and 18th). However, its ascending course has slowed down, chiefly due to the other empires rising out of its shadow. This is when Cervantes would have begun his meditation on the Catholic (Universal) Empire – a meditation that would lead him to write his great work Don Quixote de la Mancha.

As I understand it, this meditation on the Spanish empire is a task whose philosophical importance has a much further reach than the humanist meditation on the human condition, which may seem to be a much more profound meditation, but in reality is but a uniform, abstract, and empty monotony. The meditation on “Man” or the “human condition” presents itself, in effect, as a metaphysical meditation to anyone who understands that “Man” (Mankind, humanity, or the human condition) doesn’t exist outside of universal empires and that only from universal empires (that are a part of humanity, but not its whole) is it possible to make contact with this alleged “human condition.”

For a human, taken in general, is but a mere formality whose material content can only be acquired from its determinations, not in some historically universal sense, but rather through the different determinations or “modes of man” that have taken shape throughout the succession of the main Empires: from the Persian Empire to Alexander, from the Roman Empire of Augustus to Constantine and his successors – the Spanish, the English, and the Soviet. Only from the continental shelves formed by these universal empires can we begin to approach the depths of what we call the human condition, not as something invariable (except in its genetic structure common with primates) but as something ever-changing and given in the course of history. From my position, the bases of these universal empires are the most positive criteria available in order to differentiate anthropological analyses (ethological, psychological) from philosophical-historical analyses of the human condition.

In other words, the interpretation of Don Quixote as a universal figure, in the sense of being human (and what, I ask, do the so-called “values” of Don Quixote have to do with the values of a Muslim, since they too are human values?), is an empty meditation that relapses into pure psychologism.

Once we decide to develop extensively these political and historical-philosophical interpretations of Quixote, the first thing to do is to clear up the question of the extra-literary references that the stage of Don Quixote offers us, the stage through which the trinity of Don Quixote, Sancho, and Dulcinea is constantly passing.

9

The references of the characters of the fundamental trinity in Don Quixote

We must first ask ourselves how to determine the external references of the figures that appear on the stage of Don Quixote.

I will take as criterion the words pronounced from the novel’s own literary immanence, the words of one of the most significant characters who surrounds the Knight of the Sad Face: Sanson Carrasco, the “famous jester” who, embracing Don Quixote and with his voice raised, proclaimed:

“O flower of knight-errantry! O resplendent light of arms! O honour and mirror of the Spanish nation!”{21}

According to the graduate’s words (which Cervantes may very well be speaking himself), Don Quixote refers unequivocally to “the Spanish nation”. For our purposes, this has a far-reaching political meaning, demonstrating not only that the Spanish nation is already recognized in the 16th century (much earlier than the English or French, let alone the Catalonian or Basque nation), but also offering the extra-literary reference that Cervantes attributed to the figure of Don Quixote.

It’s true that the Spanish nation reflected by Don Quixote (according to the graduate Carrasco) is not a political nation in the sense that can be seen in the Battle of Valmy, as I have already noted.{22} The Spanish nation to which the graduate Carrasco refers is not a political nation that would have risen up from the ruins of the Ancient Regime, but neither is it a merely ethnic nation that either lives on the fringes of some empire or integrated with other nations in the Spanish empire. Carrasco’s Spanish nation is a historical nation whose extension matches that of the Iberian Peninsula. (When Carrasco pronounces his imprecation, Portugal makes up part of the Spanish empire – on July 26, 1582, Cervantes himself took part in a naval combat on the Azorean island of San Miguel, fighting against French mercenaries who supported Don Antonio’s aspirations to convert himself into King of Portugal). The unity and consistency of this Spanish nation could be understood beyond the then-hegemonic and visible Empire; it could be understood from France, Italy, England, and from America.

To what then does Sancho refer? He too is given to us from the same stage: a peasant from La Mancha, the head of a family made up by his wife and two children. As such, he represents any of the workers who live on the Iberian Peninsula and who are dedicated with their wives to keep their family going. Sancho, gifted with great intelligence (and not only manual intelligence, but also verbal and even literary), gets along perfectly with other peasants and people of his social status. And like them (or many of them), the well-fed Sancho (he is not a pariah from India, condemned to live a life of misery in his assigned station, even if in the presence of the “Whole”) is willing to leave his home and serve a knight who can expand his horizons, regardless of the risks that such an adventure may have in store for him.

And Dulcinea? In the words of Ludwig Pfandl nearly a century ago, “Dulcinea is nothing other than the incarnation of the monarchy, of nationality, of faith. The one-armed man [Quixote] strives for her, fighting against the windmills.”{23}

But if I were to accept Pfandl’s interpretation, wouldn’t then Dulcinea’s reference get confused with the reference that Carrasco saves for Don Quixote, the “Spanish nation”?

In some general way, yes, much as Sancho too (such as I have presented him) must refer to this same Spanish nation which now seems consolidated into, or existing as, a historical nation, regardless of the deep crisis that it is suffering after the defeat of its Armada. However, although the circumstantial reference of Don Quixote, Sancho, and Dulcinea may be the same – Spain – the perspectives from which each of these characters of the trinity refers to Spain are nonetheless distinct to each other.

10

Historical spread of the trinity of Don Quixote: past, present, and future

Perhaps Don Quixote refers to Spain from the perspective of the past, Sancho from the perspective of the present, and Dulcinea from the perspective of the future (and for that Dulcinea is a matter of faith, not of actual evidence).

These three perspectives are necessarily involved with each other, just as the trinity of Quixote are involved with each other. In other words, if each person in this stage trinity – Don Quixote, Sancho, and Dulcinea – refers to a Spain that has entered into a profound crisis, it’s because each person refers to it through or by the mediation of the others. Don Quixote is seen from a past that, even during the time on the stage, is still close (the time in which Spanish knights used lances and swords instead of harquebuses and cannons), and Sancho is seen from the present in a village that lives thanks to the fruits that the land, which must keep producing in every moment, gives after hard labor. Dulcinea represents the future, as a symbol of the mother-Spain, but I take this reference literally, which has little to do with a reference in the sense of an “ideal figure” of an “eternal femininity” and more to do with the representation of a mother able to give birth to children that as rural workers or soldiers will make the future of Spain possible.

With that said, in a historical time like that which corresponds to Spain, the present, past, and future are not mere points on a line that represents astronomical time. The time of Spain as an emerging generating Empire that is beginning to show the deep wounds that its enemies, the European predatory empires, are inflicting upon it, this time is historical time – a flowing, constantly interacting collection of millions of people, each one used to eating daily and in constant agitation and interaction. This flowing collection, this oceanic river of people who make history and are swept away by it, can be classified in three classes or circles of people theoretically well-defined:

First, there is the circle made up by people who mutually influence one another, supporting or destroying one another during the course of their lives – a circle whose diameter can be estimated as a hundred years – the years which correspond to what I call the historical present (which is not, of course, the instantaneous, adimensional present corresponding to a flowing point on the time line).

Second, there is the circle (of finite, but indeterminate diameter) made up by people who influence the people of the present for better or worse and whom we take as references, molding them nearly completely, but without us being able to influence them in any way, neither profoundly nor superficially, because they have died. This is the constituent circle of a historical past, the circle of the dead, those who increasingly tell the living what to do.

Finally, there is the circle (of indefinite diameter) made up by the people influenced by those who are living in the present, with the latter nearly molding the former entirely by marking their paths, but without the former being able to influence those who are living in the present, because they don’t exist yet. This is the circle of the historical future.

We have been supposing – or if it’s preferred, we depart from the supposition – that the references of the symbolic (allegorical) characters that Cervantes offers us on the stage of his most capital work must be placed in Spain. Spain, however, is a historical process. So to affirm that Spain is the place in which the references of the stage characters – Don Quixote, Sancho, and Dulcinea – must be placed is still not saying much.

To begin, we must determine the parameters of the present, the present in which our stage is situated, and with that perspective as a platform we can look toward both the past and the future. Undoubtedly these parameters must be obtained following the method of analysis of the literary immanence – the immanence of the stage itself, the stage on which the characters act. These indications are various and concordant and lead us to fix the date in which the characters act – the time “of the great Philip III”. Even more precisely, there is the letter that Sancho, as governor of the island of Barataria, writes to his wife Teresa Panza, dated July 20, 1614. It must be concluded then that Don Quixote took off in search of Dulcinea in those days.

This doesn’t mean though that Cervantes wanted to offer a stage which refers to the Spain of his present – a present that covers (if I maintain my hypothesis) a circle with a hundred-year diameter and which could go from 1616 – the year of his death – back to 1516, the year in which Ferdinand the Catholic died. The central point of his diameter is found very close to 1571 – the date of the battle of Lepanto, in which the twenty-four year old Cervantes took glorious part.

Cervantes didn’t propose to make a chronicle of the present in which I suppose he situated his stage. From his present, of course, Cervantes summons a stage whose reference is Spain, but not exactly the Spain of the Middle Ages (as Hegel thought when he interpreted Don Quixote as a symbol of the transition from the feudal to the modern period). Don Quixote crosses a now unified peninsula without interior borders between the Christian kingdoms and even more, without borders with the Moor kingdoms: the Spain that Don Quixote crosses is subsequent to the capture of Granada in 1492 by the Catholic Monarchs. This, therefore, is the “literary stage” (not the historical stage) of Don Quixote.

Nevertheless, Don Quixote does not yet walk across a modern Spain (Cervantes’s Spain – where the smell and noise of gunpowder were well-known, where galleons came and went to America – a Spain to which there is practically no reference in the book). In the first chapter of the book, Cervantes takes great care to tell us that the first thing Don Quixote did before leaving his house “was to clean a suit of armour that had belonged to his forefathers and that, covered in rust and mould, had been standing forgotten in a corner for centuries.”{24} Next, Alonso Quijano (who lives in the present) dressed up as Don Quixote, a knight from the past. However, this past, as is natural for every historical past, continued to heavily influence the present, for the “dead increasingly tell the living what to do”.

Nonetheless, as I have said above, Don Quixote and his group don’t operate in a medieval period, but rather in a modern one. There are no longer Moor kings in Spain. Some Moriscos that were expelled even return to Spain, and meet with Sancho:

“You don’t mean to tell me, brother Sancho Panza, that you can’t recognize your neighbour Ricote the Morisco, the village shopkeeper?”{25}

From the 1614 stage (the date of Sancho’s letter to his wife), it seems obvious that Cervantes wants to refer to the Spain of the previous century – to the Spain of 1514 that, while no longer medieval, hasn’t yet seen the arrival of Carlos I to the throne, nor above all, Hernán Cortés’s entrance in New Spain in Mexico. It seems as if Cervantes had deliberately wanted to return to a previous Iberian Spain, perhaps not before the discovery of America, but as least earlier than the massive Spanish entrance in the New World (Peru, Mexico…) and the repercussions that such an entrance would have in Spain itself.

The Spain that Cervantes sees from his novel’s stage is a Spain that neither appears as involved in the New World nor in the old continent (in Flanders, Italy, Constantinople, Africa). As such it isn’t a Spain contemplated on the scale of a coeval political society, although the stage is placed in that political society which acts as its platform. It’s as if Cervantes wanted to illuminate the references he saw from his stage; politically speaking, this is not anachronistic but simply abstract. It’s as if he wanted to illuminate with an ultraviolet light capable of revealing a civil society that continued to exist and move at its own pace in the background of the political society – a civil society with priests and barbers, dukes and puppeteers: archaic but recognizable knights-errant who, through the tricks of illumination, show up with a certain intemporal air.

This intemporal air comes from a society that, like the Spanish, has already matured as the first historical nation. Nonetheless, it still needs the care of knights armed with lances and swords, even in those moments when it is abstracted from its imminent political responsibilities (those which oblige the mobilization of armies with firearms – today we would say missiles with nuclear heads). For the interior, “intemporal” peace in which this society lives, the peace that knights believe themselves capable of finding if they dress up as shepherds, has nothing to do with celestial peace, given that bandits, murderers, thieves, liars, cheaters, and heartless, cruel scum will continue to rob, murder, steal, lie, cheat, and deceive.

When we want to come to some political interpretation of Don Quixote, how can we not take seriously this “intemporal Spain” that Cervantes would have artificially illuminated with the ultraviolet light presented above? When we try to interpret the novel from political categories, should we not recognize as Cervantes’s most significant allegorical device this “Spanish nation” that he recognized and suspended in an ultraviolet, intemporal atmosphere?

Seen as such, it seems to me that any attempt to interpret the stage of Quixote directly through immediate reference to the historical figures of its present (figures like Carlos I, Hernán Cortés, the Great Captain, or Diego García de Paredes) must be considered elementary and naïve (“A fig for the Great Captain and another for that Diego García character,” replies the innkeeper to the priest).{26}

The stage of Don Quixote refers to Spain, to the historical Spain, and to its political empire. It does so not in an immediate way, but rather through the use of an intemporal Spain, one not unreal but seen simply under an ultraviolet light in which a civil society, set in the historical time that the Iberian peninsula lives, lives according to its own rhythm.

11

Two types of philosophical-political interpretations of Don Quixote:

catastrophist and revulsive

Difficulties spring up now when we interpret the figures of Don Quixote; even supposing that their condition as allegorical symbols with ambiguous references (that play a double role in political and civil society) is admitted, as I have suggested, difficulties remain.

There are many interpretations formulated on diverse scales. The first thing that matters to us, from the historical-philosophical-political perspective that I support, is to classify these diverse interpretations in two large groups: catastrophist interpretations (or defeatist as we could also call them) and non-catastrophistinterpretations (or simply critical, or revulsive, insomuch as they interpret Don Quixote not so much as an expression of an irreversible political defeatism which could only seek refuge in a pacifist gospel – one typical of the “extravagant left” – but more as the offering of a revulsion that ends up putting weapons as the necessary (but not sufficient) condition to overcome decadence or defeat.{27}

12

Catastrophist interpretations of Don Quixote

Albeit briefly, let’s examine some interpretations of the meaning of Don Quixote belonging to the group we have labeled as “catastrophist” and in whose stock a certain “pacifist naivete” is found.{28}

According to these interpretations, Cervantes, in his fundamental work, would have supplied the most ruthless and defeatist vision of Imperial Spain that could ever have been offered up. As clever psychological critics say, Cervantes – resentful, skeptical, on the border of nihilism and disappointed by the innumerable failures that his life handed him (mutilation, captivity, prison, failure, and rejection – especially in his request to move to America, a right he felt he deserved as a hero in Lepanto) – this Cervantes would have eliminated from his brilliant novel any reference to the Indies, as well as any to Europe. The madness of the real Spanish knights (Carlos I, Hernán Cortés, don Juan de Austria) – those who supposedly ended up ruining the country – would then be alluded to allegorically by the heroes of the chivalry books that inspired the conquistadors to go to the Indies in search of El Dorado, California, or Patagonia: “To the people of Hernán Cortés,” Américo Castro says, “their triumphant arrival in Mexico seemed to be an episode from Amadís or some sort of spell”; those same books inspired them to go to England or Flanders with a squadron so archaic and “invincible” that, like Don Quixote’s own lance, was shattered in the first assault.{29}

And so if the graduate Sanson Carrasco said to Don Quixote that he was “the honour and mirror of the Spanish nation”, it’s easy to understand what he meant. For what is it that this mirror reflected? A deformed knight who goes on delirious and ridiculous adventures from which he returns defeated time and time again. Isn’t this the reflection of the Spanish nation?

Accordingly, Cervantes must be placed among those men inside the Spanish nation (not outside) who have most contributed to the development of the Black Legend (although others have done so in a much more subtle and cowardly way).{30} Bartolomé de las Casas and Antonio Peréz head this list of men, a list rounded off by the latest winner of the Cervantes Award, Rafael Sánchez Ferlosio, who in 1992 wrote a book entitled Esas Yndias Equivocadas y Malditas (Those Damned, Mistaken Indies) that was awarded the National Award for Literature under the socialist government. Nonetheless, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (1547-1616) himself must be the central figure of this list. Cervantes, with his Don Quixote, would have made a brilliant and hidden framing of the Black Legend to use against Spain while also contributing to its diffusion throughout Europe. Montesquieu would have already advised of it: “The most important book that the Spanish have is nothing other than a critique of other Spanish books.”{31}

In short, no Spaniard who maintains even an atom of national pride could see himself reflected in Don Quixote’s mirror. Only a group of people as “inflated with pride” and “charged with rights” as Spaniards (as Prat de la Riba, from Catalonia, was already saying in 1898), could identify themselves with some of the abstract qualities of the Knight of the Sad Face. Folch y Torres, another separatist who took great delight in Don Quixote’s failures (particularly insofar as these failures represented Spain’s), went so far as saying, in the same year (1898) in which “Castilian Quixotes were so crazy to declare war against the United States” (in the course of the conflicts with Cuba and the Philippines): “Let the Castilians keep their Don Quixote, for whatever he’s worth.”{32}

What’s more, this defeatist interpretation taken from Don Quixote and therefore from the interior of the Spanish empire, whereby both are the work of a megalomaniacal, cruel delirium, would not only have framed the Black Legend, but also would have fueled it as it was promoted from abroad by enemy powers (France, England, Holland) – those predatory empires and scavenging pirates that fed themselves from their infancy to their youth on the offal they went ripping off from Spain. Some suggest (recently Javier Neira) that Don Quixote‘s rapid and extraordinary success in Europe could have been due in large part to precisely its capacity to serve as fuel for the hate and disdain that Spain’s enemies wanted to direct at it.

In this defeatist interpretation, must we then follow the path that Ramiro de Maetzu himself initiated when he advised to temper the cult of Don Quixote not only in schools, but also in the Spanish national ideology?

If Don Quixote is a mad and ridiculous Spanish antihero, a mere parody and counterfigure of the real man and the real modern knight, then why is there this determination to keep him as a national emblem by celebrating his anniversaries and centennaries with such uncommon pomp? Only the enemies of Spain – internal enemies above all, like Catalonian, Basque, or Galician separatists – could delight in the adventures of Don Quixote de la Mancha.

It would still be possible to try to restore a less depressing symbolism of Don Quixote, even while recognizing his incessant defeats. We could do so by situating ourselves in the positions of the most extreme pacifism, whether it be the one defended by the extravagant left, so close to the evangelical pacifism of the current Popes (whose “Kingdom is not of this world” – thus its “extra-vagance”) or that pacifism defended by the digressive left which proclaims perpetual peace on earth and the Alliance of Civilizations. For these radical pacifists the adventures of Don Quixote could serve as an illustration, a reductio ad absurdum either in fact or in counterexample, of the uselessness of war and the stupidity of violence and the use of weapons.

Wanting to save Cervantes, the more audacious critics in this line might even dare to say that Cervantes, with his Don Quixote, has given to Spain and to the world in general an “ethical lesson” that teaches us of the uselessness of weapons and violence.

Along this line, these naive critics could see in Cervantes a convinced pacifist who tries to demonstrate the importance of evangelical peace, tolerance, and dialogue along a path of reductio ad absurdum of counterexamples – weapons that turn out to be useless, regardless of the bearer’s force of spirit.

Nevertheless, those who believe themselves capable of taking similar conclusions, “morals”, from the Don Quixote’s failures are unforgivably confused between the weapons of Don Quixote and weapons in general. This conclusion or moral is taken from the fallacious (petitio principii) premise that Don Quixote’s weapons represent weapons in general. What if Don Quixote, through his peculiar and cryptic way of speaking, were insisting on the essential difference between firearms (those with which the victory of Lepanto was obtained) and the ancient knights’ bladed weapons? According to this interpretation, Don Quixote’s failures with his rusty blades would immediately convert into an apology of the firearms that begin modern war, as seen in those first battles which Cervantes himself attended on various occasions (Lepanto, Navarino, Tunisia, La Goleta, San Miguel de las Azores).

Nevertheless, it is necessary to affirm that in any case the catastrophist interpretations of Quixote would affect Cervantes rather than Don Quixote. According to Unamuno’s thesis, a resentful and skeptical Cervantes behaved as a wretch with Don Quixote, trying time and time again to project him as ridiculous. He didn’t achieve his goal, however, and that is best evidenced by the universal admiration which Don Quixote arouses, which is not due (except for psychiatrists) to him being a paranoid madman. For as many times as Don Quixote falls down and gets beat up, so too does he pick himself up and recover; in this way, he represents the fortitude, firmness, and generosity of a knight who lives not in a fantasy world, but in the real, miserable world where he doesn’t give up when faced with misfortune.{33}

Furthermore, in no way is it clear that Cervantes held the nihilist, resentful attitude toward the Spanish empire which Unamuno attributed to him. Cervantes always maintained the pride of a combatant soldier in Lepanto, where the Holy League headed by the Spanish Empire stopped the influx of the Ottoman Empire, “the greatest occasion that the centuries saw,” as Cervantes said. In Don Quixote itself, we can also note that Cervantes approved of the Spanish policy to expel the moriscos and that he always showed himself to be a convinced subject of the Catholic Hispanic Monarchy.

In sketching his hero, Cervantes did not use the wide, elementary strokes with which King Arthur and Amadís de Gaul had been drawn throughout the centuries. Cervantes’s method was subtler. His results were without a doubt more ambiguous because of that – so ambiguous that they allowed the enemies of Spain to transform him into a pretext for derision of its history and its people.

13

Don Quixote as a revulsion

Now let’s examine some of the critical interpretations of Don Quixote that can be grouped together as revulsive.

According to these interpretations, before anything else one can find in Don Quixote a devastating criticism directed against all those Spaniards who, after having participated in the most glorious battles – those “events of weapons” in which the Spanish Empire was forged – had returned to their homes or to the court as satiate hidalgos and knights ready to live off the rent in some intemporal world, content with the memories of their glory days. They lived forgetful of the fact that the same Empire which protected their welfare, their happiness – their more or less placid and pacific life – was being attacked on all sides and starting to show alarming signs of leak after the defeat of its Armada.

After the first great push of the Empire (which is now starting to collapse), this mass of satiate people is in danger of producing the “I wan’t but can’t” of some strained knight, a knight for whom nothing is left but to wait, to wait for ridicule in trying to take up the rusty armor of his great grandparents, or the paralytic boats of the invincible Spanish Armada.

The lances and swords of his grandparents, or the bacinelmet Don Quixote himself makes, can then be seen as allegories through which Cervantes, without even needing to be aware of it, meant to represent the Spain that resulted from the ultraviolet light he used. According to this, Cervantes, with his Don Quixote, could have attempted or (if what he had attempted was to unleash his skepticism bordering on nihilism) at least could have succeeded in exercising the role of an agent of a revulsion before the government of the successive kings of Catholic majesties – Carlos I and even Felipe II, in the times of Lepanto.

What Cervantes would be saying to his compatriots is that with rusty lances and swords, with paralytic boats, with solitary adventures, or less still, dressed up as bucolic and pacific pastors, that with all of this the Spanish people would be destined to failure because the Empire that protected them and the one in which they lived was being seriously threatened by neighboring ones. Nonetheless, Cervantes would also be seeing – albeit with skepticism – that it was still possible to overcome the depression that without a doubt appeared in some of the characters – among them Alonso Quijano transformed as Don Quixote. As such, Cervantes seems to want to stress in every moment that his characters effectively have the necessary energy – even if it had to be expressed in the form of madness.

According to this interpretation, Don Quixote’s message would not then be a defeatist message, but rather a revulsive one. Such a revulsion would be destined to remove satiate Spaniards from their daydreams – those who thought they could live satisfied after the victorious battle, savoring the peace of victory or simply enjoying their “welfare state” (as Spaniards will say centuries later) provided by a new order. But this new order which Spaniards had succeeded in imposing on their old enemies came from beyond their borders – from the same America that Cervantes himself eliminates from Quixote. This perspective provides an explanation of why nothing is said in Don Quixote about everything that surrounds the peninsular enclosure with its adjacent islands and territories, of why nothing is said about America, Europe, Asia, or Africa.

As such, Don Quixote, along with his follies, would be offering some hints of the path it would be necessary to follow. The first of these, before any other, would be to travel and explore the lands of the Spanish nation: Cervantes takes care that Don Quixote de La Mancha leaves his village in the fields of Montiel and crosses the Sierra Morena. He even takes care to make him arrive at the beach of Barcelona (the same beach, it seems, in which Cervantes saw how the boat carrying his patron the Count of Lemos took off to sea towards Italy, without Cervantes being able to catch it for a final chance).

Don Quixote doesn’t cross peninsular Spain simply for fun in a “deserved rest”, nor to privately insult his people, but rather to make some sort of effort without resting (“My arms are my bed-hangings/ And my rest’s the bloody fray.”), intervening in his people’s lives, taking an attitude of intolerance in the face of the intolerable (with Master Pedro’s altarpiece, for example).{34} Or he could even be seen as inducing these lives to the fabrication of arms – not bacinelmets, but new weapons: firearms (today we would say hydrogen bombs) necessary to maintain the war that those nations hounding the Spanish will indubitably unleash if Spain doesn’t submit to them.

For Don Quixote doesn’t believe in universal harmony, nor in perpetual peace, nor in the Alliance of Civilizations. Don Quixote lives in a cosmos whose order is nothing but appearance, one that covers the profound convulsions that its parts experience, parts that never adjust to one another: “May God send a remedy,” he says in Chapter 29 of the enchanted boat, “for everything in this world is trickery, stage machinery, every part of it working against every other part. I have done all I can.”

Quixote so offers a precise message not to men (“Man” in general), but to Spanish men: an apology of arms. “War and arms are one.”{35} Let them be then, those who direct messages of hope for perpetual peace to Man in general, or to mankind, or to Humanity, because these messages will be inoffensive if we keep in mind that their recipient (humanity) doesn’t exist. A message of perpetual peace and disarmament directed to the Spanish nation would be lethal, however. It could only be understood as a message sent to Spain by its enemies, hoping that once Spain had disarmed herself, they could then go in and split her up.

In any case, it’s not necessary to suppose that Cervantes, as a finis operantis of his master work, deliberately proposed to offer a parody that would serve as a revulsion to those court favorites of the monarchy, knights of the Court, dukes, priests, or barbers in order to make them see through the adventures of a grotesque knight where their complacency, their welfare, and even their literary taste for knights-errant or the pastoral life could lead them.

It’s sufficient to admit the possibility that Cervantes could have immediately perceived a particular kind of madness in the hidalgo whom he called Alonso Quijano and who was driven mad by reading chivalry books. Cervantes undoubtedly found an interest in both his condition as madman and, even more so, in the nature of his madness; there is very little in common between the madness of the licenciado Vidreiera and Don Quixote’s madness, although the differences between the two end up grossly erased when they are considered only in their common denomination as “madmen”. The madness of the latter resembled enthusiastic knights of the court such as Amadís or Palmerín, and even Hernán Cortés and the Great Captain, although Cervantes may have wanted to separate these last two, diverting attention towards the first two so as not to raise uncomfortable or dangerous suspicions or divert the direction of his reductio ad absurdum demonstration.

To summarize – in this nobleman gone mad by books of chivalry and converted into a knight – “a knight armed with derision” – Cervantes could have sensed the ridiculousness of those happy and complacent knights who fueled themselves on old stories. Even further, it can be conceded that this allegory – suggested from the beginning, but in chiaroscuro – became a constant stimulus for the author and gained momentum as it went, driving the author to dedicate himself with greater fervor to the development of such an ambiguous character, one so ambiguous that it became inexhaustible – a character that promised so much, even from its initial, simple definition.

The hectic development of his brilliant invention – that is, the discovery of “a nobleman from La Mancha mad for his effort to turn himself into a knight-errant” – could be, of course, the river bed that gathered the powerful current pouring into Cervantes. This current undoubtedly had been around some years before Don Quixote came to be, gathering resentments, let-downs, and slights towards knights, court favorites or satisfied dukes: all those national heroes who, living in a fully “welfare state”, took joy remembering their own or others’ heroic memories while chatting away on their hunts or in their salons, be it in Madrid, Valladolid, or in Villanueva de los Infantes.